- Edition: An Humorous Day's Mirth

Textual Introduction

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Facsimiles

1Title

In the Oxford History of English Literature, G. K. Hunter lists George Chapmanʼs play as ‘A Humorous Dayʼs Mirth (1597)ʼ. This simple statement combines the two different lives of the play: on stage (the date) and in print (the title). In the summer of 1597 John Chamberlain wrote to Dudley Carleton: ‘We have here a new play of humours in very great request, and I was drawn along to it by the common applause, but my opinion of it is (as the fellow said of the shearing of hogs) that there was a great cry for so little woolʼ.[141] A play named as ‘the comodey of vmersʼ was entered as ‘neʼ in Hensloweʼs diary on 11 May 1597.[142] The same play is also referred to as ‘the vmersʼ and performed a further ten times before the July break, on 19, 24, 31 May, 4, 7, 11, 17, 21 June, and 7 and 13 July; Henslowe also records performances on 11 October and 4 November of the same year.[143] ‘The Umersʼ is also among the play-books Henslowe lists as having bought since 3 March 1598.[144]

2The key pieces of information linking this play to the printed text of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth lie in two inventories of goods taken by Henslowe on 10 and 13 March. Among the descriptions of various costumes is ‘Verones sonnes hosseʼ and ‘Labesyas clocke, with gowld buttenesʼ;[145] the hose and cloak belonging to two characters specifically unique to An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth. This information led F. G. Fleay to identify the performed ‘comedy of humoursʼ with the text printed as An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth by Valentine Simmes in 1599; this is supported by the title page information identifying it as an Admiralʼs Men play.[146]

3Hunter records the play under its printed title, but adjacent to the year of first recorded performance, thus muddling the performed and printed life of the text. The printed title is remarkably straightforward and descriptive, alerting the reader to the playʼs diurnal framework and its comedic play on charactersʼ humours or temperaments. The performed title heralds a new comic genre. Martin Wiggins has identified this play as the first of the new humours comedy, of such influence on the genre of comedy as to equal Tamburlaine‘s effect on tragic form.[147]

4The question as to whether the authorial title should take precedence over the theatrical one is a philosophical one.[148] Indeed, it is not possible to determine whether Chapman or the printing house was responsible for the printed title. The choice involves either giving precedence to the playʼs performed title, or identifying the printed text as the only true witness and closest to the author. Alternatively, one can incorporate both titles.

5Dating the Play

Although An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth was not entered in the Stationersʼ Register, Hensloweʼs records note the first performance of a play known as ‘the comodey of vmersʼ on 11 May 1597.[149] Accepting Fleayʼs association of this reference with An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, May 1597 becomes the upper limit of estimated composition.

6Chapmanʼs previous hit for Henslowe, The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, was playing at the Rose theatre from 12 February 1595 until 1 April 1597, according to Hensloweʼs own records. He seems to have been planning a revival of it, since further records in 1601 note payments made for its clothing. An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth shows Chapman clearly drawing on his first comedyʼs experimentation with humours used by one character to disguise himself in three specifically characterised roles. Chapman extends this motif to a play whose comedy is based solely on humours, and, as such, is the first play of its kind. Since An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth develops themes explored in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, and from Hensloweʼs evidence of performance chronology, it is safe to ascertain that the composition of The Blind Beggar of Alexandria preceded that of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth. The play is therefore dated 1597, year of first performance, unless the printed text of 1599 is specifically referenced.

7Sources

Of all the sources noted for An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth the most proximate to its creation is Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, dated 1595 by Martin Wiggins, and 1594-5 by the playʼs most recent Arden editor, H. R. Woudhuysen.[150] The latter admits that links between Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost and An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth are ‘flimsyʼ, yet Wiggins suggests that ‘The attentive eye may detect tracesʼ of Shakespeareʼs play in Chapmanʼs comedy.[151] Among the similarities noted by Woudhuysen between the two plays are the show, or lottery in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, ‘presented by a Boy who is extensively interrupted, during which a maid is revealed to be already pregnantʼ.[152] Woudhuysen notes the similarity between the name of the maid in Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, Jaquenetta, and her corresponding double in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, Jaquena, as well as the names Lemot and Moth, both of which facilitate puns on words and motes. Finally noted is Chapmanʼs use of the ‘proverbial titleʼ in Scene 6: ‘My lord, my labour is not altogether lostʼ (TLN 737; see also the introductory section on Language ).

8Lemotʼs courting of Florila in Scene 6 bears striking similarities to the wooing of Francesco Vergellesiʼs wife by Zima in Boccaccioʼs Decameron.[153] An English translation did not appear in print until 1620, although the Decameron was available in Italian and French. Closest in date to the composition of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth were copies printed in Italian in 1594 and 1597, and three French translations printed in 1579 and 1597. Jonson uses the same story as source material for The Devil is an Ass (1616), also printed before the English translation of the Decameron became available, suggesting that both playwrights may have read it in another language, or that the story was available in English in some other format.[154] Baskervill suggests that stories from the Decameron were being incorporated in jestbooks, which in turn provided source material for jigs. A Hundred Merry Tales contains the story ‘Of the wife who lay with her prentice and caused him to beat her husband disguised in her raimentʼ, or Decameron 7.7, which is remarkably similar to the jig entitled ‘Rowlandʼs Sonʼ.[155]

9Zimaʼs successful wooing of Francescoʼs wife occurs within sight, but out of earshot, of Francesco, in similar circumstances to Lemotʼs tempting of Florila to put on her best attire and meet him at the ordinary. In the source, Zima tricks Francesco by talking to the lady, who is not allowed to say a word, and articulates her imagined response to his advances. He notes her glowing eyes and emotive sighs in response to his words, and concocts a plan: when Francesco has left for Milan on business, the lady will place two towels at the window of her room, overlooking the garden, as a sign for Zima to come to her at night, via the garden door, and consummate their love. Similarly, Florila agrees certain signs with her husband before she is ‘testedʼ by Lemot, but, in full sight of her husband, she reinterprets one of these signs for Lemot:

I told my husband I would make these signs:

If I resisted, first, hold up my finger,

As if I said, ‘iʼfaith, sir, you are goneʼ,

But it shall say, ‘iʼfaith, sir, we are oneʼ.

(TLN 719-721)

10Florila dutifully performs the other signs, stopping Lemotʼs lips, pushing him away and offering her handkerchief ‘to wipe his lips/ Of their last disgraceʼ (TLN 745-746), purely for her husband's reassurance.

11A similar situation occurs in Spenserʼs Faerie Queene (1590), Book 3, in which the elderly Malbecco is married to a beautiful younger woman, Hellenore. Spenserʼs description of Malbecco is one that equally serves Labervele, and all older, jealous husbands:

But he is old, and withered like hay,

Vnfit faire Ladies seruice to supply;

The priuie guilt whereof makes him alway

Suspect her truth, and keepe continuall spy

Vpon her with his other blincked eye;

Ne suffreth he resort of liuing wight

Approch to her, ne keepe her company,

But in close bowre her mewes from all mens sight,

Depriu'd of kindly joy and naturall delight.

(3.9.5)

12The spying and protective jealousy of Labervele is also manifest in Malbeccoʼs character. Like Florila and Francescoʼs wife, Hellenore circumvents her husbandʼs protectiveness using special signs which she exchanges with the attractive younger male, Paridell, who has caught her eye. While Florila reinterprets pre-agreed signs and Francescoʼs wife flashes her eyes and sighs to communicate with Zima, Hellenoreʼs secret signs to Paridell include spilling wine, ‘By such close signs they secret way did makeʼ (3.9.31).

13While Florila is prevented from committing adultery because of Lemotʼs deceit, and Francescoʼs wife enjoys a fulfilling secret relationship with Zima, Hellenoreʼs story is much less fortunate. Once she has run away with Paridell, he abandons her, leaving her to be taken in by satyrs, who are attentive to all their chargeʼs needs, sexual and otherwise. In comparison, it is clear that while Lemot tempts Florila, he violates only her Christian purity; sexually she remains untainted, unlike Hellenore. Lemotʼs petitions are false and he abandons Florila once she has committed herself to him, but, unlike poor Hellenore, Florilaʼs fate is contained within the boundary of mirth. The incident thus serves as a stark warning, both to Florila, against temptation, and for Labervele, to turn his back on jealousy and trust his wife.

14Chapman appears to undermine Florilaʼs devout Puritanism by having her quote ‘Habbakuk the fourthʼ (TLN 417), a non-existent chapter of the Bible, since Habbakuk has only three chapters. The chosen book enables Labervele to explode with jealousy by aural association with cuckoldry: ‘Cuck me no cucks!ʼ (TLN 418). Later, when Lemot has bitten Florilaʼs hand, he admonishes her for bad behaviour, urging her back to her husband with the words ‘Go, Habbakuk, goʼ (TLN 1468), which sarcastically remind her of her supposed Puritan wisdom and piety.

15Another foolish character, Labesha, enters with a quotation in Scene 11 as part of his affected melancholic state. Copying Dowsecer in Scene 7, Labesha quotes in Latin. Although the source has been identified as a misquotation of Nigellus Wirekerusʼs Speculum Stultarum, the phrase also appears in Lilyʼs Grammar (1540) to explain the relative case, thus confirming Catalianʼs suspicions: ‘you shall hear him begin with some Latin sentence that he hath remembered ever since he read his accidenceʼ (TLN 1509-1511). Dowsecer, whom Labesha imitates, quotes not from his school grammar book, but from Ciceroʼs Tusculan Disputations upon his entry in Scene 7.

16Lemotʼs statement at the beginning of the play explains his intention to assume a royal position and ‘sit like an old king in an old-fashion playʼ (TLN 43-44). He continues by quoting from Thomas Prestonʼs Cambyses, King of Persia (1561), ‘My council grave...ʼ (TLN 46). In I Henry IV, written during the twelve months preceding the first performance of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, Sir John Oldcastle announces that he will play the part of Halʼs father in their role-play ‘in King Cambysesʼ veinʼ (2.5.390).

17The few sources selected by Chapman to supplement his comedy fall into two distinct categories: those mined for quotations to be placed in the mouths of his characters, and those which may have provided inspiration for the plot. They also supply a healthy cross-section of available Elizabethan source material, including classical, biblical and pedagogic writings, as well as secular influences from medieval prose and early drama through to contemporary poetry and very recent theatrical influences. The direct quotations have been carefully chosen for each character: Cicero confirms Dowsecerʼs stoical sympathies whilst also exemplifying his intellectual reputation; Labesha, in contrast, proves his idiocy by aping Dowsecer, choosing to recite Latin any school boy could remember from his grammar book, and thus demonstrating a lack of continued intellectual vigour since school; Florilaʼs devout Puritanism is undermined by choice of a chapter which doesnʼt exist from a biblical book which does, highlighting an erroneous knowledge of the Bible cloaked in piety. Similarities noted between An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth and Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, minor as they are, point to a similar, if unintentional, unveiling of the playwrightʼs own influences, in which plot device and word play are plundered for Chapmanʼs comical effect. For further discussion, see ‘Languageʼ.

18Printerʼs Copy

There is evidence to suggest that the copy for Q was an authorial, pre-theatrical manuscript, so the textual witness may not representatively record the successful script of the Roseʼs popular play. The evidence for this includes Gregʼs reference to the ‘careless abbreviationʼ of speech prefixes;[156] Yamada adds the ‘inconsistent nomination of characters in the stage direction.ʼ[157] The abbreviation of speech prefixes is complicated by the use of one or two letters which might signify more than one character: for example, Catalian, Colinet, and Countess may be signified by ‘C.ʼ, while ‘La.ʼ causes confusion for Labervele, Labesha, and Lavel. Yamada lists examples of speech confusions, and inconsistent entrances and exits, which further suggest that the copy used by the compositor was unlikely to have been a pre-theatrical manuscript. Allan Holaday remarks that the stage directions are inexplicit and, on occasion, do not mark the entrance of a principal character.[158] The lack of sound effects supports the theory that the copy is of non-theatrical origin.

19Seven stage directions have been printed in the margins of Q. Holaday asserts that these stage directions are not Chapmanʼs additions, but that they must have been inserted to reduce staging errors. They may have been written in the margins of the manuscript and faithfully reproduced by the compositor. Alternatively, Chapman might have been aware of how dramatic insertions were made and copied this marginal format. He may also have been revising the ‘fair copyʼ of the manuscript before delivery to the theatre, from which the prompt copy was usually made.

20General Characteristics of Q

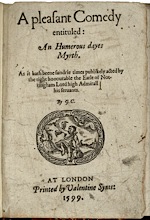

Only one quarto edition of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, printed in 1599, survives at the present time in seventeen extant examples; it is does not appear to have been recorded in the Stationersʼ Register. The play quarto contains thirty unnumbered leaves and collates as follows: A-G4 H2. Gregʼs bibliographic description is numbered 159. The title page can be described thus:

A pleasant Comedy/ entituled: / An Humerous dayes / Myrth. / As it hath beene sundrie times publikely acted by / the right honourable the Earle of Not- / tingham Lord high Admirall / his seruants. / By G. C. / [device 142] / AT LONDON / Printed by Valentine Syms: / 1599.[159]

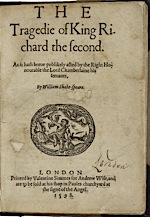

21Device 142 features a ‘boy with wings on one arm and the other holding a weightʼ,[160] and is also found on the title pages of other plays printed by Valentine Simmes, including Shakespeareʼs Richard II (1597 and 1598).

The first page of text, A2, is headed with an ornament commonly used by Simmes in this place, and also featured in Richard II (1597), Richard III (1597), 2 Henry IV (1600), and Hamlet (1603). Above the colophon on H2r, Simmes uses a type ornament. The title page names no publisher or bookseller, and the authorʼs initials ‘G.C.ʼ have been identified as referring to George Chapman without question.

22Valentine Simmes, Printer

Valentine Simmesʼs printing career is chequered with incidents. Although at first apprenticed to the bookseller Henry Sutton he was transferred at his own request to the printer Henry Bynneman, and was presented for his freedom in 1585 by Bynnemanʼs widow.[161] He attracted attention from the authorities for printing undesirable material and books belonging to others. In 1589 he was in trouble as a compositor of the Martin Marprelate press, and in 1595, while printing the ‘Grammar and Accidenceʼ, his press was seized, type melted, and apprentice transferred. Again in trouble in 1599, the year An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth was printed, he was listed among fourteen printers forbidden to print satires or epigrams. Despite such trouble, Simmes printed over twenty plays, at least ten of which are by Shakespeare. The only other extant edition of a Chapman play printed by Simmes is The Gentleman Usher (1606).

23Greg describes the type used in Simmesʼs printing house as ‘ordinary roman and italic type of a body approximating to modern pica (20 ll. = c. 82 mm)ʼ.[162] Upper case italic was short, and since the compositor preferred to set all speech prefixes in italics, he often had to resort to roman type, especially letter L, which was in frequent use.

24Compositorial Analysis

After running several types of test on An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, Yamada identifies no more than two, and probably only one, compositor at work on the play.[163] Holaday agrees, and cannot prove a second compositor with orthographic tests.[164] However he highlights D1v and D2, where examples of misreadings and eyeskips hint at the involvement of a second compositor, who also seems to have trouble with the Latin at this one place in the text. Yamada records spelling and punctuation favoured by the compositor, as well as interesting examples of the above.[165]

25Alan E. Craven describes the unusual preferences of a compositor in Simmesʼs shop, known as Compositor A.[166] The tendency of Compositor A not to place a full stop after unabbreviated speech prefixes, or use contrasting type for proper names, suggests that he was not the compositor who set An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth.

26Proof-State Sheet G and Stop-Press Correction

Yamada records the existence of a proof-state copy of the outer forme of sheet G in the Bute copy held at the National Library of Scotland.[167] His article reproduces the four corrected pages, manuscript additions clearly visible, arranged in comparison with the corrected printed sheets. At the point when Yamada wrote his article, he had examined fifteen extant copies of the play. Seventeen copies have been identified to date, and the NLS copy is still the only one to exist in the uncorrected state, all other copies having sheet G in the corrected state.

27From the proof-state of sheet G Yamada infers that ‘stop-press corrections seem to have been a practice of Simmesʼs shopʼ.[168] He also concludes that the corrections were made in the early stages of the formeʼs printing and that it was likely that the whole forme had been corrected on a single occasion. Yamada notes that the corrector sought to change punctuation marks, correct basic errors, and make some attempt to regularise spelling preferences. However, his task was not carried out entirely thoroughly, nor did he mark letters that were badly inked or printed from worn type. Yamada deduces that the corrector must have consulted his copy due to the addition of ‘atʼ (G1, l. 31), but failed to notice other similar errors.[169] Nevertheless, Yamada acknowledges the insight such ‘invaluable evidenceʼ as a proof-state sheet offers into proof-reading practice.[170]

28After perusal of the press variants listed for sheets A, B, D, F, H, and especially sheet G, proof correction can be identified as a regular practice of Simmesʼs shop. Stop-press correction affected sheet A (outer and inner), sheet B (outer and inner), sheet D (outer and inner), sheet F (outer and inner), sheet G (outer) and half-sheet H.

29Running Title

Holaday and Yamada agree that two skeleton formes were used in the printing of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, one each for the outer and inner formes. Several characteristics of the first half of the running title, ‘An humorousʼ, enable the use of these two skeleton formes to be traced through the printing of the play. As Holaday points out, sheet A needed setting with a title page and was therefore set specially.[171] The running titles were then transferred from sheet A to the skeleton formes for sheet B.

30To begin with, the outer forme is set with a pair of running titles, one of which has a swash A for ‘Anʼ (B2v) and one with a distinctive ‘uʼ and ‘usʼ ligature at B4v. The inner forme has a pair of running titles, which spell ‘humerousʼ with an ‘eʼ instead of an ‘oʼ, as in the outer pair. The re-usage of all but the swash ‘Aʼ running title of sheet A (as A1v is blank, being the verso of the title page) is evident in sheet B, although the outer skeleton has been transferred to the inner forme in the setting of sheet B. The skeleton formes are used consistently in this way for the inner and outer formes until sheet E, where the skeleton for the outer forme is used ‘upside downʼ and the spelling of ‘humerousʼ in the inner skeleton forme has been altered to ‘humorousʼ, as identified by Holaday.[172]

31At sheet F the outer skeleton forme is returned to its usual orientation (as in sheets B-D). By sheet G the outer skeleton forme has been altered once again, the joined ‘usʼ being removed but the distinctive ‘uʼ remaining in G4v. The spelling of ‘humorousʼ continues in sheets F and G in the inner skeleton forme after its alteration at sheet E.

32Setting of the Quarto

In order to determine whether the play was set by forme or in seriatim, the printed quarto was studied for signs of space saving and wasting. These signs can indicate that the compositor had been adjusting the text to fill the pages designated by the casting off procedure, which primarily informs the printer how much paper is required, and is also useful in allowing formes to be set non-consecutively.

33The average page of text consists of thirty-six lines of type, including the text and stage directions embedded within it, but excluding those in the margin. Three exceptions were the first page of text (A2), which features the play title and an ornament, and two pages in which text had been placed in the same line as the catchword (G2v and G3v). Of the remaining pages, one had four white lines (F1v), while two pages had three white lines (B4 and C3). These three pages and their respective formes have been analysed in order to determine whether the use of white lines seemed to correlate with wasting space allocated to that forme. Indications of space saving, which may have impacted on the decision to insert white lines, have also been noted.

34F1v (inner forme) has four white lines, each placed before stage directions. If these are thought to waste space, the stage direction at the top of the page confirms this: ‘Countesseʼ could fit onto the first line of the stage direction, but the compositor chooses to fill two lines. A similar example can be noted on F3v where a three-line stage direction might have squeezed into two lines. Here there are no white lines before or after the stage direction. However, on F4 certain lines of text have been tailored to fit onto one line. Lines 18 and 29 both have considerably, though not unusually, abbreviated speech prefixes: ‘Laberveleʼ becomes ‘La.ʼ while ‘Lemotʼ is signified ‘Le.ʼ for the only time on F4; elsewhere on the page he is signified as ‘Lem.ʼ The text of l. 18 only just fits the line, while the text of lines 28 and 30 have no final punctuation. A mark at the end of l. 28 looks like an accidentally inked quad.

35It is more likely for a compositor to set the text as economically as possible before discovering the need to waste space by expanding the text and inserting white lines at the end of the forme. Since the compositor could set pages of the cast off formes in any order there was no need for him to observe the numerical sequence. This may suggest that F1v was the last page of sheet F (inner forme) to be set, since it is the page on which space wasting is to be found.

36Sheet B (inner forme) also suggests that space was used carefully on certain pages, but wasted elsewhere in the forme. On B1v, effort is made to save space: the last line of Florilaʼs first speech (l. 10) occupies an entire line without final punctuation. The use of an ampersand and the shorter spelling ‘therforeʼ is also of note. At l. 27 ‘Laberveleʼ is shortened to ‘La.ʼ to accommodate a line which also spells ‘womenʼ with a tilde: ‘wom{~e}ʼ.

37Sheet B (inner forme) also suggests that space was used carefully on certain pages, but wasted elsewhere in the forme. On B1v, effort is made to save space: the last line of Florilaʼs first speech (l. 10) occupies an entire line without final punctuation. The use of an ampersand and the shorter spelling ‘therforeʼ is also of note. At l. 27 ‘Laberveleʼ is shortened to ‘La.ʼ to accommodate a line which also spells ‘womenʼ with a tilde: ‘wom{~e}ʼ.

38In comparison, B3v and B4 are very different in their composition, particularly the latter. Florilaʼs words on B3v at ll. 11-12 could occupy one line, but the compositor has inserted extra spaces. Similarly, the final two lines of Lemotʼs long speech illustrate not an excessive utilisation of space, but the lack of need to economise: ll. 28-29 could have squeezed into one if the spelling ‘farreʼ had been shortened and a tilde been used in ‘reputation.ʼ Space is used liberally on l. 36 with additional spaces inserted between words so that ‘sayʼ appears at the top of B4, a word which could have been accommodated on B3v. B4 itself has three white lines, one before and two surrounding stage directions.

39Sheet C (outer) bears fewer marks of spatial problems. The main point of note occurs on C3 where two stage directions are flanked by two and one white line respectively. However, these may signify a wish on the part of the compositor to break up the long speeches of text which appear as solid blocks to the eye.

40A survey of stage directions revealed that while eighteen stage directions had white lines before, four had them before and after, and twenty-seven stage directions had no white lines at all, although four of these could be explained due to their placement at the top or bottom of a page. It is difficult to conclude whether the compositor preferred to set white lines before stage directions and therefore used none when space was scarce, or whether he only inserted white lines to waste space, and preferred setting stage directions without. It is also possible that the compositor preferred to set white lines before stage directions at the beginning of a new scene, where there might be a corresponding break in the manuscript.

41A brief study of individual inner and outer formes reveals patterns of space-saving and space-wasting, indicated by lack of punctuation, alteration of spelling, insertion of white lines and larger spaces between words and punctuation, which suggests adjustments being made to fit text into the pages unset between already composed formes. Of course, casting off also helps estimation of the length of the text and thus the amount of paper required for printing. It is also more likely that setting by formes was employed, as opposed to ‘seriatimʼ, when two compositors were working on one text. However, as Philip Gaskell observes ‘setting by formes appears to have been a common practice in English and in some continental printing up to the mid seventeenth century.ʼ[173] Gaskell also suggests setting by formes helped printers make use of a limited stock of type.

42Half-Sheet H

The most complex bibliographical intrigue concerning the extant copies of this play resides in half-sheet H, which exists in three states, two of which are preserved in single copies. Thirteen copies of the play include a corrected form of half-sheet H,[174] while the Eton copy alone preserves the text in its uncorrected form. The BL1 copy contains a very different state of half-sheet H, which does not feature in the chronological correction of the text. It has not been ‘correctedʼ, rather ‘reprintedʼ, using a wider measure and, Greg suggests, a different font. He proposes that some sort of accident caused the last three pages to be reset.[175] Pieing is improbable as an explanation because both formes are involved.[176] Greg suggests that either a short run of half-sheet H was printed, or that the printed stock was accidentally destroyed, prompting a reprint. In order for this to be probable, the type set for the original copy must have been redistributed by the time of destruction, necessitating the resetting of the half-sheet.

43The chronological production of the three states must have begun with the printing of the ‘uncorrectedʼ state (Eton copy), followed by correction and the printing of the ‘correctedʼ state (BL2 and others). The third state of the text (BL1) must have been printed after the other two. No further theory can be posited without specific information concerning the activity of the printing house.

44Half-Sheet Imposition

Another possible explanation for the existence of BL1 half-sheet H is half-sheet imposition, which would require that the two variant states of the text were set and printed simultaneously. Gaskell identifies two methods of printing half-sheets:

In one, called half-sheet imposition, all the pages for a half sheet were imposed in one forme ... this forme was first printed on one side of the whole sheet, then the heap of paper was turned (end over end in quarto and octavo...) and printed from the same forme on the other side. Each printed sheet was then slit in half to yield two copies of the same half sheet. In the other method, the pages for two successive half sheets were imposed in two formes and printed in the normal way; again the printed sheets were cut in half, but this time each one yielded copies of the two successive half sheets which were different from each other, but which were sometimes indistinguishable from similar half sheets printed by half-sheet imposition.[177]

45If half-sheet imposition was employed to set half-sheet H, it cannot have been by the first method outlined by Gaskell, as ‘work and turnʼ produces two identical copies of the text for each sheet of paper printed. The two states of half-sheet H for An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth are anything but identical. K. Povey identifies a way of printing two copies of a half-sheet by half-sheet imposition from one sheet of printed paper.[178] This involves setting each page twice and imposing it in two formes. The paper is printed with the first forme and perfected with the second forme. Each sheet is cut in two, yielding two copies of the half-sheet for each sheet of paper printed. Using this method two very different states of the text can be produced simultaneously, without the need for Gregʼs accidental destruction theory. However, this new suggestion requires examination.

46The wider setting of the text and running titles both suggest the possibility of half-sheet imposition. Also striking is the ornament on H2 before the colophon: in the BL1 copy, seven and a half repetitions of the pattern are used, while in the corrected state (e.g., BL2), only six and a half repetitions of the same pattern occur, with an additional half-repetition of a different pattern. It would seem unprofessional for a compositor to use an incomplete, mismatched ornament on one state when a complete set of ornamentation was obviously available in the printing house, as the BL1 state indicates, unless the two states were printed at the same time. In this case the compositor might be stretched for ornamental type, if setting two copies of the same text simultaneously. Furthermore, the ornament does not appear in A Warning for Fair Women, also printed in 1599 in Simmesʼs shop, and signifying that the ornament was not in use in the only other extant play printed by Simmes that year.

47Also puzzling is use of a wider measure and different font. This irregularity might indicate the work of another compositor, one who had not previously worked on the text of the play, and who might have his composing stick set to a different measure. There are no stage directions in sheet H, so no comparison of the treatment of stage directions in the two states could be made. Spelling preferences can sometimes identify the work of different compositors, so a comparison of BL1 and BL2 copies was made. Words spelt differently in the two states of half-sheet H were then traced through sheets A-G to accumulate the spelling preferences of the compositor who set the rest of the play. Of course, the quantity of text set on half-sheet H is very small and the tests conducted were inconclusive because only one example of differentiation existed in either state of the text. Also, when a compositor has a preference for one spelling, he invariably also uses the non-preferred spelling at some point in his setting. The following results were found:

| Preference | Non-preference | BL1 | BL2 |

| selfe (29)[179] | self (5) | selfe (1) | self (1) |

| maner (3) | manner (1) | manner (1) | maner (1) |

| husband (16) | husbande (2) | husbande (2) husband (1) | husbande (1) husband (2) |

| sweete (14) | sweet (7) | sweete (2) sweet (1) | sweete (3) --- |

| shall (68) | shal (18) | shall (2) shal (1) | shall (1) --- |

48Very little can be established from this analysis due to the small sample of spellings in half-sheet H; however there are some signs that where the rest of the text established a strong preference, BL2 follows it, but the other copies (represented by BL1) do not. This suggests, if anything, that the same compositor set the rest of the play plus BL1ʼs ‘resetʼ half-sheet H and a different compositor set the half-sheet H found in the other copies. However, the test does not take into account the influence of justification on spelling preferences. Wishing to avoid the pitfalls of scant evidence, the investigation is deemed inconclusive.

49Watermarks

A study of the watermarks in three British Museum copies indicates that one type of paper was used throughout the printing of sheets A-G, bearing the watermark of a pot.[180] At sheet G in BL1, the watermark changes to a hand and flower, which is used for all of the printing of half-sheet H. However, the use of the same stock of paper in the resetting of half-sheet H does not necessarily imply anything definite. Simmes may have used a lot of paper bearing this watermark in his shop, rendering estimation of time lapse between printing of the original and reprinted half-sheet H impossible. Secondly, the reprinting may have occurred within a very short space of time of the initial half-sheet H being printed. However, the use of paper with the same watermark for sheet G and half-sheet H does not rule out the possibility of half-sheet imposition, and goes some way to support it. If half-sheet imposition is ruled out, the type must have been redistributed into the cases before it was realised that more copies were needed.

50Study of both copies of the play in the New York Public Library yielded a potentially interesting piece of evidence. The copy in the Arents Collection had evidence of a liquid stain of perhaps an inch deep along the bottom edge of H1 and H2. However, the pages belonging to sheet G possessed no evidence of any stain at all, as might be expected had the liquid damage occurred whilst the play was sewn. This suggests that half-sheet H in this copy had been stained before it was sewn or allocated to its edition. The stain supports Gregʼs suggestion that the stock of half-sheet H was damaged or destroyed in some way, therefore prompting resetting of the half-sheet.

51Although half-sheet imposition is a good idea in theory, it is to be doubted whether a compositor would have regularly employed such a time-consuming practice. Furthermore, D. F. McKenzie warns against assuming that one compositor and one press dealt with a single book at a time. McKenzieʼs study of the Cambridge University Press records indicates that one compositor might spend time setting at least two books at a time, or even that different compositors would be swapped onto one book, whilst also jointly setting other books.[181] It seems that without the records of Simmesʼs shop it would be very difficult to reach any conclusion other than a speculative one. It is only known that Simmes also printed A Warning for Fair Women in the same year. But as has already been mentioned, his record is not clean: in 1595 his presses were confiscated and his type was melted down, while in 1599 he was on a list of printers who were banned from printing satires, so Simmes was obviously printing material other than the plays which survive.

52Press Variants

Despite W. Carew Hazlittʼs claim that ‘There were two issues of this drama in the same year: the other purports to have been “Printed by Valentine Syms for John Oxenbridge”ʼ,[182] not even W. W. Greg has been able to trace more than one extant edition. The word ‘purportsʼ suggests that maybe Hazlitt had not seen the copy in person, and raises the possibility that it was being held in a private collection. The 1599 edition survives in seventeen copies, which are held at the following institutions (an asterisk indicates copies visited):

| BL1 | British Library C.34.c.14* |

| BL2 | British Library C.12.g.4* |

| BL3 | British Library Ashley 369* |

| Bodl | Bodleian Library |

| CLUC | William A. Clark Library, University of California at Los Angeles |

| CSmH | Huntington Library |

| CtY | Beneicke Library, Yale University |

| DFo1 | Folger Shakespeare Library #1* |

| DFo2 | Folger Shakespeare Library #2* |

| Dyce | Victoria and Albert Museum |

| Eton | Eton Library |

| GWU | Glasgow University Library |

| Kingʼs | Kingʼs College Library, Cambridge* |

| MH | Houghton Library, Harvard University |

| NLS | National Library of Scotland* |

| NN1 | New York Library, Arents Collection* |

| NN2 | New York Library, Berg Collection* |

53Of these seventeen copies, Greg only refers to BL1-3, Bodl, Dyce, Eton, ‘while at least three are in Americaʼ.[183] In his detailed article ‘Bibliographical Studies of George Chapmanʼs An Humorous Dayʼs Mirthʼ, Akihiro Yamada collates all except CtY and Kingʼs. Allan Holaday (1970), collates ten copies: BL1, Bodl, CLUC, CSmH, CtY, DFo1, Dyce, GWU, Kingʼs, and MH.[184] For this edition, Holadayʼs collation has been thoroughly checked. The remaining seven copies have been collated and a list of press variants compiled in consultation with the lists of Holaday and Yamada. In both lists there are a number of errors and omissions which have been corrected. Holaday identifies only two corrected states of sheet B (outer forme) because of neglecting to collate NN2, which preserves the third state. A reprint of half-sheet H exists in BL1, differing from all other copies in size of measure, font and spelling. The press variants recorded by annotations in the text do not include these differences, which have been recorded by Yamada elsewhere.[185]

54Not all seventeen copies are complete: Kingʼs and DFo2 lack half-sheet H. In both, the final half-sheet of the play is copied by hand from the first state of half-sheet H. Yamada names W. Henderson responsible in DFo2, in which the copying is more accurate than in the Kingʼs manuscript of half-sheet H, which alters spellings and, occasionally, words. Kingʼs is also lacking sheet E, as well as C1 and C1v, although no compensation has been made for this in manuscript form. DFo1 lacks A1, and the title page has been copied by hand, without an attempt at reproducing the device. The variant noted on sheet D (inner forme) D1v is the first record of its existence, as is the variant on H1v, l. 9 and the complicated sequencing of variants found on sheet F (outer forme).The existence of a copy of proof-state sheet G (outer) provides clues to stop-press correction in Simmesʼs shop. For an extended discussion, see ‘Two Textual Issues Originating in the Printing Houseʼ.

55Editorial Practice

‘Comedies are writ to be spoken, not read: remember the life of these things consists in actionʼ.[186] So John Marston reminded his reader in his preface to The Fawn, thus emphasising the importance of theatrical manifestations of dramatic texts. This edition has aimed to realise Marstonʼs assertion within the boundaries of an editorial format. Consideration has been made of original staging practice and conditions, including costume, properties and use of the stage space. This has informed the commentary and introductory discussion in order to provide useful material to guide readers as well as theatre practitioners. It is hoped that theatre practice of the past might aid understanding of the text, thus facilitating fresh consideration of the dramatic opportunities presented by this text.

56The edition also tries to bear in mind that not all users will be aided by practical, dramatic engagement with the text. Therefore stage directions have been inserted both to inform the reader of what is happening, as well as guide actors. The edition places stage directions in what is considered the most sensible place: the choice is explained and alternative options given. It is hoped that such interventions are neither too prescriptive nor certain in their claims.

57This text provides the editor with an opportunity to develop a full commentary, with references to and differences from Charles Edelmanʼs excellent recent Revels edition (2010).[187] Parrottʼs notes provide helpful explanatory and bibliographical information, but are far from adequate. Holadayʼs sparse notes cover textual matters only. This editionʼs commentary tries to consider what Michael Cordner identifies as the ‘intricate interplay between the verbal and the visualʼ.[188] The aim is to suggest multiple interpretations of language, intonation and dramatic action. However, as Cordner accurately identifies of Shakespearian texts: ‘Annotation cannot, of course, track all the possible, plausible, performance extrapolations which have been, and could be, madeʼ.[189] On the other hand, he warns against editors ‘prematurely delimitingʼ the exciting potential of Renaissance texts to provide opportunity for exploration.[190]

58It is initially the editorʼs job to research and illuminate these possibilities at the same time restoring the textʼs performative capabilities and functionality as a theatrical script, a task which necessarily begs alterations and emendations. These notes cannot be limited to aiding the theatre practitionerʼs understanding and performance of the text but must also provide a useful guide to the reader, visualising the art of the playwright and his devised stage business. In his Apology for Actors, Heywood identified the gap between text and performance, and the need for there to exist a symbiotic relationship between the two: ‘A description is only a shadow received by the ear but not perceived by the eye: so lively portraiture is merely a form seen by the eye, but can neither show action, passion, motion, or any other gesture, to move the spirits of the beholder to admirationʼ.[191] The editorʼs task is therefore to reconcile reading of the text with action, and vice versa, to enable action both onstage and in the readerʼs mind.

59In the final unifying, revelatory scene of the play, a lottery is held, hosted by Verone but engineered by Lemot, at which jewels and posies are handed out. Martiaʼs posy warns her: ‘Change for the betterʼ (TLN 1946), which sage words also serve as an editorial reminder: a reminder of his/ her procreative power and responsibility to provide clarifying, but not limiting, emendations of the text.

60Character Names

When considering standardisation of speech prefixes, Stanley Wells advises the adoption of the modern form of a name, unless other demands are made by the metre.[192] In cases where no modern form exists, he suggests looking for the commonest spelling used in the most authoritative early text, in this case, the 1597 quarto. Because Chapmanʼs play is set in France, some of the names require thought as to their modernisation.

61The key reason for modernising names is to establish a standard label of reference for a character or place. Consideration of previous editorial decisions provides helpful starting points: Shepherd does not always settle with one speech prefix, alternately using Host and Verone, Besha and Labesha, Puritan and Florilla. This is obviously undesirable since it defeats the purpose of modernising a name as part of the standardisation process. The abbreviations of speech prefixes employed by both Shepherd and Parrott are also deemed undesirable, especially given the similarity of many names in the play. These include Labervele, Lavele, Labesha, the Countess and a couple of Counts, not to mention Catalian and Colinet, whose names all provide room for confusion in Q, which also confuses Mor(en) and Mar(tia) on B4 and D4.

62Some character names, such as Verone, Catalian, Berger, Martia, Foyes and Jaques, either have standard forms or are referred to consistently in Q. Jaquena, who is consistently identified as ‘Maidʼ in the speech prefixes is identified by her name rather than her occuptatio, following Edelman. Lemot, meaning ‘the wordʼ in French, might recommend that this is more obviously presented in his name, by changing it to ‘Le Motʼ. In this edition, as in all previous editions, the Q form ‘Lemotʼ has been retained, since the component parts of the French name are quite clear, and glossed in the list of characters.

63Labeshaʼs name is less straightforward, since he is often referred to as Besha in the text, speech prefixes and in the stage directions in Scenes 3 and 5. Thomas L. Berger, William C. Bradford and Sidney L. Sondergardʼs Index of Characters in Early Modern English Drama is keen to segregate component parts of names. Thus they list Le Mot and La Besha alongside La Vache, La Feu (Allʼs Well That Ends Well) and the more familiar Le Fer (Henry V), Le Beau (As You Like It), and La Brosse (Conspiracy of Byron). In Q, Labeshaʼs name is always printed as one word, rather than two, and all editors have followed suit. It is thought clear enough that ‘Beshaʼ refers to the character also called ‘Labeshaʼ. Further explanations of character names accompany the list.

64Prose and Verse Lineation

The quarto compositor/s set the majority of the play as prose, excepting lines at TLN 153-154 and couplets at TLN 1928-1929, TLN 1933-1934, and TLN 1956-1957. However, as previous editors have identified, passages of verse are discernable amongst the prose. Although Chapman tends to write in blank verse for this play, the iambic pentameter is at times rather loose and occasionally difficult to distinguish from prose. Sometimes the looseness of the metre suggests that perhaps Chapman was intending to return to these passages for further work. Another possibility is that the play was written as prose in Chapmanʼs manuscript and that the compositor was not so much saving space and paper as copying exactly the manuscript in front of him.

65The intention has been to set as verse any passage that appears to scan metrically, although sometimes the metre is very loose iambic pentameter. Passages set as verse by Parrott and rejected by Holaday have been reintroduced where considered appropriate. Examples of difficult passages, in particular Scenes 4 and 6, have been annotated in the notes. Edelman offers a useful discussion of the options open to editors and resists converting the quartoʼs prose to verse in many cases.[193] Edelman concludes that ‘characters usually speak in verse when they are “humorous”ʼ and uses this as his ‘guiding principle in editing the textʼ.[194]

66Chapman allocates prose to higher status characters, such as the King, a feature uncommon in plays of this period, except perhaps in Lylyʼs prose plays. In Shakespeareʼs Henry IV plays, the prose/verse lineation serves as a social indicator: tavern scenes are set in prose while court scenes are written in verse. In An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth the allocation of verse and prose seems to signify difference between characters and their relationships with each other in more complex ways.

67Of particular note is the relationship between Florila and Labervele. In Scene 4, Florilaʼs first appearance, the control she exercises over her emotions, senses, actions and thoughts, manifests itself in her language, which is delivered in verse. When her husband enters, the dialogue continues in verse, reflecting the high style of Florilaʼs histrionic response to the jewels. Even when he enters the stage on his own, Labervele speaks in verse, as in Scene 1. The tight control of the verse begins to break down into prose when Laberveleʼs suggestion that Florila have more of a social life is met with eager response. Laberveleʼs aside at TLN 250-252 is in prose, and the pairʼs subsequent lines until TLN 268 are conducted in prose, indicating Laberveleʼs loose power over his wife, and Florilaʼs willingness to embrace society, despite her usually feisty words against it.

68At the entry of Catalian, Labervele once again reverts to verse, almost as if trying to gain control over the situation. Catalianʼs persistent prose suggests that the control is gradually being wrested from Labervele, and also indicates the slipping of Florila from a woman of extreme morals to the hypocritical Puritan who willingly succumbs to temptation. By the time of Lemotʼs entrance at TLN 310, Labervele does not attempt to confront the new intruder with a barrage of verse, after which point Lemot is allowed private but overlooked access to Florila and the opportunity to tempt her with vain suggestion.

69The content of Scene 6 is almost entirely regulated by Laberveleʼs watchful eye and the verse in which the scene is written. This suits both the high wooing style of Lemotʼs words to Florila and the regulatory style of the content in which the testing of Florila is key. The verse is the controlling mechanism of the test, without which the words spoken by either character would be liberated. Despite this, the verse is still more relaxed than the Marlovian style. The fact that Florila reinterprets the signs, another safety measure designed to control the test and give Labervele greater confidence in his wife, and the manipulation of language by Lemot, ensures that the rules of the test are followed, but Labervele is verbally cuckolded right in front of his eyes.

70Scene 6 is almost entirely in verse, apart from a confused five line section, which has been treated differently by each previous editor. This section, TLN 722-728, has been set as a mix of verse and prose detailed in the annotations accompanying the text at this point.

71Two other characters who notably speak in verse appear in the next scene. Scene 7 opens with the Kingʼs melancholic reflection on kingship. Lemot quickly changes the tone to prose revelation of a ‘royal sportʼ (TLN 801). The contrast is made between metrical, melancholic philosophy and unruly, illicit intrigue. Dowsecer, similarly melancholic and contemplative, speaks almost entirely in verse in this scene, apart from his attempt to court the picture at TLN 918-922. Labervele, whose fondness for verse has been noted earlier, conducts a conversation with his son in verse. The verse itself is not precisely metrical, but rather loose, with too many syllables in certain lines, prompting the possibility that Chapman intended to rework these passages.

72Chapman also chooses to write some of Scene 12, particularly Lemotʼs lines, in verse. In this scene he artfully chooses words to mislead the Queen into thinking her husband no longer fancies her and that his penis is about to be amputated. The clever game of predicting other charactersʼ words which has been practised in Scene 8 is more expertly contrived in this scene, prompting Foyes, Labervele and the Countess each to inquire after a particular person in Lemotʼs narrative, only to discover the person is their daughter, son and husband. Lemotʼs use of verse signifies his control over metre, language, content and other charactersʼ reactions. Occasional lapses into prose are made by the Countess, who rants in isolation about her husbandʼs infidelity, and the Queen, who is shocked by Lemotʼs purposefully misleading revelations.

73The King regains control from Lemot after the play, and soothingly wraps up the action with suggestion of a party to celebrate the misunderstandings and smooth over any wounds. The rhyming couplet with which the play concludes is a standard feature of the ending of Renaissance plays, but also contains the numbing effects necessary to tranquilize any fiery tempers and ensure a joyful celebration of mirth.

74Punctuation

The punctuation of the Quarto lightly guides the reader towards meaning. Yamada notes that the compositor was keen to use commas and full stops, but mainly the former.[195] This edition has sought to avoid the over-punctuation favoured by Parrott and Shepherd, particularly in the liberal use of semi-colons and exclamation marks. The intention has been to punctuate lightly, aiding the userʼs understanding of difficult passages whilst hoping not to reduce alternative interpretations; options are available discussed in the notes. Certain decisions involving punctuation require a simple commitment to a particular reading of a line. In particular, Scene 1 presents problems of interpretation due to the complex nature of Laberveleʼs discourse and syntax, coupled with the setting of the scene in prose, when it was clearly written in verse. Laberveleʼs speech is sprinkled with commas where the userʼs understanding is better guided with more decisive punctuation.

75TLN 1091-1092 prompts a discussion of punctuation, not because the subject matter is especially complex, but simply in deciding the inflection of the line. Each previous editor has chosen different methods of conveying this. Q reads, ‘giueʼs the cardes, here come, this gentleman and I wil go to cardes while dinner be ready.ʼ Berger is addressing Verone, the host, and referring to his companion, Rowley. The effect of the comma after ‘comeʼ is as a caesura in the line, before Berger informs Verone of his intention to fill the time with a game of cards, and this is the sense conveyed by Parrottʼs edition: ‘Giveʼs the cards here, come!ʼ Bergerʼs intention is separated from his call for the cards.

76Shepherd places a full stop after ‘cardsʼ, suggesting that the second thought is entirely separate from the first, when the Q reading seems to indicate an order followed by explanation. Shepherdʼs punctuation of the line infers that Berger calls for the cards, then has the idea of playing with Rowley while dinner is prepared. Holaday places a semi-colon after ‘hereʼ, so that ‘comeʼ relates not to the instruction given to Verone, but again to the notion that he will play with Rowley. This edition follows Edelmanʼs decision: ‘Comeʼ is part of an invitation to Rowley rather than the imperative command for the cards. Any of these choices can be supported with suitable reasoning, yet the final editorial decision cannot accommodate all possibilities. In this case, as in several, it is sensible to weigh up the arguments, make a decision and support it with explanation and other options.

77Scene Division

An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth is not divided into scenes and is the only one of Chapmanʼs plays to be thus printed, apart from The Blind Beggar of Alexandria. Both these plays were written for Hensloweʼs outdoor theatre, which required no acts or scenes, unlike plays written for the indoor theatre, in which act divisions were a requirement to enable the candles to be trimmed. Scene divisions were introduced into the next printed Chapman play, All Fools (1605), which was written for an indoor theatre.

78Parrott was the first of the playʼs editors to insert scene divisions. There are two differences between his scene labelling and that of this edition: Scene 8.5 (this edition) is labelled Scene 10, and therefore a separate, rather than part of a continuous, scene; Scenes 13 and 14 (this edition) are combined and become Scene 14 (Parrott). Holaday opts to divide the play into acts and scenes. If scene divisions are to be imposed on a play to segregate dramatic action and facilitate easy reference, there is no need to further insert act divisions, since the former are sufficient for this purpose. This edition has decided to point to the continuity of action from Scenes 8 to 8.5. Scene 9 seems to occur elsewhere (see ‘Above Spaceʼ). The stage is not cleared after 8 and therefore a method of making this clear to the reader was required. Dividing the scene into two parts, a) and b), seemed the most appropriate method, where 8 refers to the part of Scene 8 occurring before Scene 9, and 8.5 refers to the four lines spoken after it.

79Scene 10 poses problems which challenge the usual requirements for a new scene, the rule for which is described by Gurr and Ichikawa: ‘A break between Shakespearian scenes generally begins with the exit of all characters, and the new scene opens with the entrance of other characters.ʼ[196] Scene 10 involves groups of characters entering and exiting very quickly after speaking only a few lines. This rolling action is of a kind that does not require separate scene labels, but is part of one scenic sequence. Therefore, scene breaks have not been inserted to segregate the action. Gurr and Ichikawa further helpfully comment on how this rolling action effect might be achieved:

It is reasonable to assume that the closing exit of one scene and the opening entrance of the next are made through different doors. Variations on this pattern might, however, occur where the exit at the end of one scene and the next sceneʼs entrance overlap.[197]

80It makes sense in Scene 10 for characters to enter through one door, speak their lines, and hurry offstage through another door, while the next group of characters enter through the ‘enteringʼ door.

81Editorial Procedures

Of the seventeen extant copies of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, BL C34.c.14 (BL1) was chosen as the control copy for this critical text. Substantive press variants have been noted and corrections made to the text where appropriate. Other copies have been consulted particularly for the transcription of half-sheet H, the copy of which is unique in BL1.

82The aim was to produce a modern-spelling edition of the play, edited according to the principles set out by Stanley Wells in Modernizing Shakespeareʼs Spelling. Words have been modernized in accordance with their lemma in the OED. Any words with ambiguous spellings have been carefully considered and spelt to convey their primary meaning. Any alternatives have been recorded in the notes accompanying the text. Some silent emendations have been made, such as, ‘thenʼ for ‘thanʼ, and vice versa.

83‘Andʼ meaning ‘ifʼ, by itself or in the phrase ‘and ifʼ, has been altered to ‘anʼ in clear cases, but where there is some doubt ‘andʼ has been retained, in accordance with Wells. ‘Enowʼ has been modernised to ‘enoughʼ for, despite once signifying a plural, it no longer has such significance.

84Of the long list of press variants, only a handful of substantive alterations were necessary, most of them being alterations to punctuation or spelling. The exceptions are: much] more (TLN 214), would] will (TLN 239), more deeply] most deepely (TLN 371).

85Punctuation has been altered in order to clarify the sense for the modern user of the text. The collation details substantive alterations, particularly when meaning might be affected. Location descriptions are mentioned in the notes at the beginning of a scene when specified by dialogue.

86Stage directions from the control text have been retained and additional directions added only to clarify stage action for the user. Where a variety of staging options are involved, they have been discussed either in the commentary or at an appropriate place in the Introduction. Alterations and insertions appear in square brackets. The six stage directions that appear in the margin of the control copy have been moved to a logical place within the text. Their authority is unknown, but they aid comprehension of the text.

87At the bottom of C2r (TLN 595-596), the stage direction ‘Enter Lemotʼ appears in the margin despite Lemot already being present in the scene. This edition concurs with Holaday that this direction failed to be removed from the skeleton when transferred from inner B to inner C and therefore does not reproduce it from the Quarto.[198] Turned or obviously incorrect letters in the control text have been silently emended. Speech prefixes have been treated as labels and made uniform in accordance with Wells to avoid the confusion which arises from a text such as Shepherdʼs, where one abbreviation can signify more than one character.

88‘Puritanʼ has been capitalised when thought to refer to a member of the Puritan movement; when referring to a puritanical character, the word remains uncapitalised. Likewise, Devil is capitalised when referring to the actual Devil, as in Satan, but is uncapitalised when the reference is more general, literal or metaphorical. All quotations have been silently modernised except where a point is made which old spelling will illustrate.