77Melancholy

Perhaps one of the most frequently referred to humours, both physiological and affected, is that of melancholy. In Galenic terms an overabundance of black bile, this humour is commonly identified as gentlemanlike, and thus affected by characters such as Stephano, who worries ‘Am I melancholy enough?ʼ (2.3.99-100). Fastidius Brisk and Sogliardo announce they will affect melancholy in 5.2 of Every Man out of His Humour at the death of Puntarvoloʼs dog, but Macilente dismisses their planned affectation as ridiculous. Miola quotes Jonsonʼs commendatory poem to Nicholas Bretonʼs Melancholic Humours (1600), in which he acknowledges the difference between genuine melancholics and those ‘wearing moods, as gallants do a fashion,/ In these pied times, only to show their brainsʼ.[70]

78Unaware of these criticisms, Stephano introduces himself to Bobadilla and Matheo as ‘somewhat melancholyʼ (2.3.71-2), as a clumsy indication of his gentlemanly status. Matheo indulges Stephanoʼs affectation by agreeing that ‘itʼs your only best humour, sir. Your true melancholy breeds your perfect fine wit, sirʼ (ll. 80-81). Matheo continues by sympathising with Stephano: he too suffers from melancholy and occupies his afflicted time with writing ‘your half-score or your dozen of sonnets at a sittingʼ (l. 84). Matheoʼs false affectation is of course rendered all the more deceitful when he is exposed not as an original poet, but one who copies other poetsʼ work and claims it as his own.

79Labesha similarly affects a very self-conscious form of melancholy when he discovers that the woman he idolises, Martia, has attended the ordinary. After informing her father of her whereabouts, he announces his intentions:

I will in silence live a man forlorn,

Mad, and melancholy as a cat,

And nevermore wear hat-band on my hat! (TLN 1398-1399)

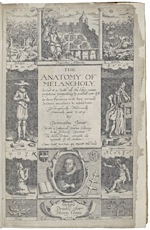

80 The frontispiece to Burtonʼs Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) shows the melancholy lover with hat pulled down and his arms folded. References to the lover abound in Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, where Moth describes him thus: ‘with your hat penthouse-like oʼer the shop of your eyes, with your arms crossed on your thin-belly doublet like a rabbit on a spit, or your hands in your pocket like a man after the old paintingʼ (3.1.15-19).[71] Lemot describes Blanvelʼs humour as the repetition of words spoken ‘to a syllable after him of whom he takes acquaintanceʼ (TLN 66), and his retreat to the wall or chimney, ‘standing folding his armsʼ (TLN 76-77). Perhaps this indicates that Blanvel, like Labesha, is also affecting the melancholy lover. In Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, Berowne refers to Cupid as ‘lord of folded armsʼ (3.1.176). In the Induction to Every Man out of His Humour, Asper asks Mitis if he can spot a melancholic gallant, who ‘Sits with his arms thus wreathed, his hat pulled here,/ Cries mew, and nods, then shakes his empty headʼ (ll. 160-61).

81When the melancholic Dowsecer enters quoting Cicero, he is communicating that his sympathies lie in Stoic philosophy, thereby lauding reason and the suppression of all strong emotions. Dowsecerʼs entrance is preceded by that of the King, who expresses anguish at his own lack of reason: ‘And such are all the affections of love/ Swarming in me, without command or reasonʼ (TLN 779-780). This is the first time that Lemot and the King are together onstage, and it is clear that while the King suffers from similar stoical agonies as Dowsecer, Lemotʼs task is to boost the Kingʼs mood and distract him from these melancholic thoughts.

82 Indeed, when Dowsecer enters and begins to speak, his monologue is interspersed with approving comments from the King. The quotation from Cicero also helps to explain Dowsecerʼs musings not simply as melancholic, but as stoical. The sword and items of apparel placed before Dowsecer prompt speeches declaring his dislike of the irrational, while the picture is rendered safe from wounding his affections because of the superficiality of painting which also occupies Hamletʼs mind. However, when Dowsecer comes into contact with a real woman, Martia, the strong emotions he has been attempting to keep in check overwhelm him: ‘What have I seen? How am I burnt to dust/ With a new sun, and made a novel phoenixʼ (TLN 962-963).

83Dowsecer next enters in Scene 14, utterly transformed into a passionate lover: ‘Iʼll geld the adulterous goat, and take from him/ The instrument that plays him such sweet musicʼ (TLN 1704-1705). The other characters onstage assume Dowsecer refers to the King, since he is with Martia, but this suggestion confuses Dowsecer. The identity of the ‘adulterous goatʼ is therefore unknown, as is the catalyst for Dowsecerʼs sudden, angered appearance. Perhaps this omission points again to a pre-theatrical copy text.

84In Scene 11, Labesha is seen fulfilling his claim, affecting melancholy in the vein of Dowsecer in Scene 7. Like Dowsecer, Labesha begins his speech with a Latin quotation, but his contemplation is interrupted by espial of the cream and spiced cake left in his path by Verone, Catalian and Berger. These are eaten with appetite and forced protestations from Labesha, who pretends he is eating to choke himself as an act of suicide. The choice of cream and spiced cake is perhaps an upmarket version of beer and toast provided by some alehouses as a snack.[72] It also serves a medicinal, corrective purpose of possessing the hot (cake) and wet (cream) properties which should help balance black bileʼs cold dryness. The food provides a joke at the expense of Labesha: according to Galenic principles it should help rebalance his humours and relieve him of his melancholy, except that his humour is falsely self-imposed.

85When Verone devises the plot to tell Labesha that Martia has drowned herself, Catalian, who has assimilated Lemotʼs gift for predicting behaviour, exclaims that Labesha will probably hang himself at the news. The joke is brought to fruition with the appearance of Labesha with a halter about his neck in the final scene. It is unknown whether Labesha had been wearing the halter to inspire sympathy, or whether his loss of Martia prompted a real intention to commit suicide, like Sordido the grain speculator of Every Man out of His Humour. Sordido attempts to hang himself onstage, but is rescued by a number of rustics, just as Labeshaʼs intention to commit suicide is interrupted by Lemot. Labesha reluctantly succumbs to the Kingʼs promise of a better wife for him, but there is no suggestion that his character has gained the insight to change.

86On the other hand, Sordido overhears the rustics cursing him. He realises they hate him and blames his humour: ‘It is that/ Makes me thus monstrous in true human eyesʼ (3.2.104-5), vowing to change his behaviour, and dig up all the grain he had hoarded from his children and the people. He is privileged in taking part in a plot which drives the characters towards self-knowledge, the recognition of wrong-doing, change and reconciliation.