26The ‘comedy of umersʼ

Although it is now generally accepted that Hensloweʼs record of a box office hit called the ‘comedy of umersʼ is Chapmanʼs printed play, An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, it is less widely accepted that Chapman was the instigator of the genre entitled ‘comedy of humoursʼ. Despite a steady voice amongst Chapman scholars attributing him with the creation of the first play of this type, Chapman is often accredited with little more than putting the idea in Jonsonʼs head, and producing work with much room for improvement. Baskervill points out that although in simplistic terms either of the aforementioned playwrights might be credited with inventing the comedy of humours genre, really the development sprang from numerous sources of dramatic and medical literature.[27] As far back as 1567 Baskervill finds extensive use of the word ‘humourʼ in Geffraie Fentonʼs translation of Bandello as Certain Tragical Discourses (1567).[28]

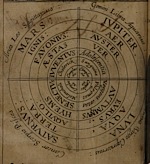

27In the Elizabethan period, the order and machinations of the earthly world received scholarly and theological scrutiny based on ancient and medieval studies. The pyramidal ordering of the created universe placed God at its apex, his authority filtering through the monarch, as head of created society, to the lords, gentry and the lower classes. Extensive study of astronomy and astrology charted the impact of the universe on menʼs lives, in the correct timings for the planting of vegetables and herbs, government by the seasons and the cyclical pattern of the moonʼs orbit. Study was also made of the organization and operation of the body, and it is here that humoural theory was employed.

28In the Induction to Every Man out of His Humour, Asper describes ‘humourʼ thus:

Why, humour (as ʼtis, ens) we thus define it

To be a quality of air or water,

And in itself holds these two properties:

Moisture and fluxure.

(Induction, ll. 86-89, Revels edition)

29Thus, humour was a constantly flowing bodily fluid. Galenʼs theory of humours describes four bodily fluids: black bile, yellow bile or choler, blood and phlegm. These humours were not equally present within the body, but existed in specific proportions, blood being the predominant. If one humour was present to a greater or lesser degree than the perfect balance, imbalance would present itself in a temperamental manifestation, rendering the person melancholic, choleric, sanguine or phlegmatic, thus lucidly described by Asper:

As when some one peculiar quality

Doth so possess a man that it doth draw

All his affects, his spirits, and his powers

In their confluxions all to run one way:

This may truly said to be a humour.

(Induction, ll. 103-07, Revels edition)

30Thus humoural theory was a physiological and psychological explanation for a personʼs temperament, also called ‘humourʼ. Usage of the word increased throughout the second half of the sixteenth century.

31Chapman had experimented with humoural differences when writing The Blind Beggar of Alexandria (1596), the doctored text of which exists in a quarto dated 1598, which strips down the romance plot, preserving mainly the comic interludes. The title page boasts that the blind beggar in question, known as Irus, will be ‘most pleasantly discoursing his variable humours in disguised shapes full of conceit and pleasureʼ. Chapman used the stock plot ingredient of disguise to explore duplicity, aided by humoural traits. Irus plays not only the part of the blind beggar, but also three other characters: Count Hermes, Duke Cleanthes, and Leon the usurer. Chapman made use of garments and humoural disposition to distinguish between the characters played by Irus. Long before Nym was proudly using the new catchword ‘humoursʼ in The Merry Wives of Windsor (1597-8), Bragadino in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria was doing exactly the same thing.

32Overt use of humours in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria has led Robert S. Miola to call it Chapmanʼs trend-setting humours play.[29] However, while Chapman indeed uses humoural temperament as an accessory to characterisation, sketches stressing a characterʼs vice of folly were already popular in the work of Nashe and Lyly.[30] Chapmanʼs innovation in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth was to increase the emphasis on temperament in characterisation, and use this as the basis of the entire plot. Lemot announces ‘this day letʼs consecrate to mirthʼ (2.59) and the resulting action pivots on ‘the underlying premise that people are in themselves funny enough to sustain a comic actionʼ.[31] Chapman does not rely heavily on the medical or theoretical aspects of humours, preferring instead to focus on temperamental differences. Shakespeare, and, to a greater extent, Jonson, were innovators of the new comedy, including references to medicinal humoural theory to increase comic characterisation. In a paper entitled ‘Shakespeareʼs Comedy of Humorsʼ, Northrop Frye begins: ‘The phrase “comedy of humors” belongs to Ben Jonson, so that a paper with such a title has to begin with the relation of Jonsonʼs comedy to Shakespeareʼs.ʼ[32] This introduction argues that since the phrase rightly ‘belongsʼ to George Chapman, any discussion of Ben Jonsonʼs humoural drama should begin with the former playwright.

33Chronologically, Chapman precedes Jonson by experimenting with humours in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, performed in 1596. At a similar time as Chapman offered An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth to the Admiralʼs Men, Jonson is thought to have produced The Case Is Altered for Pembrokeʼs Men.[33] The repetitious catchphrase for the latter play provides its title, and the alteration of charactersʼ states perhaps fed Jonsonʼs more brutal idea for Every Man out of His Humour‘s systematic purgation of humours. Jonsonʼs well-known response to Chapmanʼs invention, Every Man in His Humour (1598), was probably not the first, nor can The Case Is Altered pose any claim as first humours play.

34The text of Jonsonʼs first surviving comedy, The Case is Altered, was not printed until 1609 and bears evidence of revision, which is thought to have occurred in 1601. This revision principally involves the addition of the character Antonio Balladino, who represents Anthony Munday and rails against the established genre of humours comedy. Jonsonʼs revisions self-consciously attempted to modernize his first play with additional references that cannot have been included in the first performed version, because the genre attacked had yet to be established.

35It seems that Shakespeare was the first to respond to Chapmanʼs humours play by offering The Merry Wives of Windsor to the Chamberlainʼs Men, followed by Much Ado About Nothing (1598). Jonson, who had joined the Admiralʼs Men after the disastrous fall-out over The Isle of Dogs (1597; co-written with Nashe), now had access to, and perhaps contact with, Chapman and his work. Indeed, when the theatres reopened, having escaped threatened demolition in response to Jonson and Nasheʼs lost but presumably seditious play, Chapmanʼs humours comedy was chosen, along with Doctor Faustus and ‘Joroneymoʼ, to encourage audiences back to the Rose.[34]

36Andrew Gurr points to the influence on comedy of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, among other plays, as ‘possibly the clearest single indicator of the power and intensity of the commercial incentive in company repertories through the whole period.ʼ[35] The Chamberlainʼs Men benefited from Shakespeareʼs development of the humours genre in The Merry Wives of Windsor and Much Ado About Nothing, and Jonsonʼs Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Every Man out of His Humour (1599). Henry Porter offered Henslowe The Two Angry Women of Abingdon (1598), while Chapman apparently continued his satire of sartorial affectation in his lost play, The Fountain of New Fashions (1598). The events of summer 1597 might have almost forced the end of lawful drama in London, but without it, and the amalgamation of Pembrokeʼs and the Admiralʼs Men, forcing Jonsonʼs association with Chapman, the genre of comedy might not have received such a radical overhaul at the latter playwrightʼs hands.

37Suddenly, plays containing references to humours on their title pages abounded: The History of Henry the Fourth ... With the humorous conceits of Sir John Falstaff (1598); The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, most pleasantly discoursing his variable humours in disguised shapes full of conceit and pleasure (1598); A pleasant Comedy entitled: An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth (1599); The Pleasant History of the Two Angry Women of Abingdon, with the humorous mirth of Dick Coomes and Nicholas Prouerbs, two Servingmen (1599); The Comical Satire of Every Man out of his Humor (1600); The Shoemakersʼ Holiday, Or the Gentle Craft, with the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoemaker, and Lord Major of London (1600). As Jason Scott-Warren astutely observes, ‘Humor rapidly became a marketable commodityʼ.[36] The dramatic tide had turned.