- Edition: An Humorous Day's Mirth

Critical Introduction

- Introduction

- Texts of this edition

- Facsimiles

1George Chapman (1559-1634): 'The best for Comedy'

In a quiet corner of a once marshy and disreputable corner of London, in St Giles-in-the-Fields church, a monument stands to ‘Georgius Chapman, poetaʼ. Originally positioned in the yard on the south side of the church with the inscription ‘Georgius Chapmanius, poeta Homericus, Philosophus verus (etsi Christianus poeta)ʼ it was later brought inside the church where it stands today, with a new inscription cut under direction by the then Rector. Created by Inigo Jones after Chapmanʼs death on 12 May 1634, the once magnificent but now weathered and scarcely legible tribute stands to the man who contributed translations of Homer, poems, comedies and tragedies to the growing body of Renaissance literature. Yet the material which inspired Keats to write his well-known sonnet and prompted T. S. Eliot to plan an unwritten essay received mixed reception, both during Chapmanʼs life and in more recent critical discussion.

2Wealth evaded Chapman, causing financial trouble in the form of loans and lawsuits, but also prompting the creation of dramatic triumphs. It has been suggested that were it not for Chapmanʼs desire to work on his translations and the need to fund this endeavour, the rich literary treasures of his plays, in particular his comedies, might not have been manifested on paper or transmitted into print. The Blind Beggar of Alexandria and An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth in particular provided Philip Henslowe with box-office hits, and payment for Chapman.

3Indeed, despite publishing his first known work The Shadow of Night in 1594 at the advanced age of thirty-four, it was only four years later that Chapmanʼs labours received praise from Francis Meres. In 1598, Meresʼs Palladis Tamia, Wits Treasury was printed, listing Chapman as one of ‘the best for Comedy amongst usʼ along with Lyly, Greene, Shakespeare, Nashe, Heywood and Chettle.[1] Chapman is also listed among the best for tragedy, along with Marlowe, Shakespeare and Jonson, although none of these early tragedies have survived.

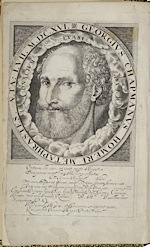

4Basic facts concerning Chapmanʼs life are few. A description of Hitchin, Hertfordshire as his ‘native airʼ in the ‘Inductioʼ to The Tears of Peace identifies Georgeʼs birthplace, where he was born as second son to Thomas and Joan Chapman. An engraving featured in The Whole Works of Homer depicts a bearded man and enables an estimation of his birth year: the encircling inscription states that Chapman was fifty-seven in the year 1616, thus estimating his year of birth as 1559.

5Despite Anthony Woodʼs assertion that Chapman went up to Oxford, no other confirmatory record has been found to support this. Jean Robertson cites Phyllis Brooks Bartlettʼs point that ‘If he had studied the ancient tongues at Oxford, surely he would never have boasted that he was self-taughtʼ, which he does in the Epilogue to the Hymns of Homer.[2] Unlike Shakespeare, Chapman had a plentiful knowledge of Latin and Greek, as his translations surely testify. Upon the death of their father, Thomas, the elder son, inherited the house and land, while George received one hundred pounds and two silver spoons. As two significant lawsuits illustrate, pecuniary need was to plague Chapman for much of his life.

6An inscription found in a copy of Batrachomyomachia asserts that Chapmanʼs ‘youth was initiateʼ in the house of ‘Ralph Sadler Esquireʼ.[3] A Chancery case filed in 1608 provides extra information concerning these years. It alleges that Chapman borrowed a sum of money from the convicted fraudster John Wolfall, the bond of which was dated 12 July 1585.[4] This detail is confirmed in Chapmanʼs 1608 bill of complaint against John Wolfall the younger, in which he explains the reason for the loan: ‘then having occasion to use a sum of money to furnish himself ... fit for his proper use in attendance upon the then Right Honourable Sir Ralph Sadler Knightʼ.[5] Chapman estimates that the bond was made roughly twenty-five years before, i.e. 1583, in order to serve Ralph Sadler. Sadlerʼs properties included Standon Hall, Hertfordshire, Duchy House in the Strand, London, as well as a manor house in the Hundred of Hitchin at Temple Dinsley. Although Sadler died in 1587, Chapman may have continued his service to the Sadler family beyond this date.

7Two years later, in 1589, Chapmanʼs father died, leaving him the aforementioned money and spoons. It may have been this money which aided him to travel overseas, occupying some of the unknown years between service for Sadler and his first publication, The Shadow of Night, in 1594. The Chancery case also provides information volunteered by Wolfall the younger that his father had not pursued the bond due to ‘the absence of the saide complainant by yonde the seasʼ.[6]] This supports any suggestion that Chapman had spent some time abroad, time enough to prevent the elder Wolfall from collecting his bond. Chapman was active as a published poet and playwright in London from 1594 until 1600, when he was arrested for debt by Wolfall.[7]

8It therefore makes sense to suggest, as Eccles has done, that Chapmanʼs period abroad occurred between the end of his service with Ralph Sadler and his poetic activity in London. As we cannot be sure when Chapmanʼs attendance upon the Sadlers ceased, despite knowing him to be in service in circa 1585, this must be the earliest date conjectured for his travels. It is more likely, or at least possible, that Chapman remained in Sadlerʼs service until the latterʼs death in 1587. Robertson further claims that Chapman was likely to have been in England at the time his fatherʼs will was proved on 5 June 1589.

9A further, more specific suggestion regarding Chapmanʼs activity abroad is based upon evidence in Hymnus in Cynthiam in The Shadow of Night.[8] It is suggested that Chapman served as a soldier during campaigns in the Low Countries, as did Ben Jonson, and in particular was present at Sir Francis Vereʼs ambush of Spanish troops at Nymeghen. The date of this exploit was 24 July 1591, thus falling within the estimated window of dates when Chapman is likely to have been on the Continent. Jonathan Hudston also suggests that further evidence of Chapmanʼs military service is to be found in the dedicatory letter to the Crowne of all Homers Workes which describes ‘an episode at Ghent in 1582ʼ.[9]

10Eccles alternatively proposes that Chapman could have spent time in France, a popular destination for Elizabethan travellers. He points to the fact that ‘Chapman showed his special interest in France by choosing the subjects for five of his six surviving tragedies from French historyʼ (p. 190), not to mention An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, which was set in Paris. This is not necessarily an indication of Chapmanʼs experience as a traveller, since, as Eccles also points out, it is known that Chapman had access to Edward Grimestoneʼs translation of Jean de Serreʼs Inventaire Général de lʼHistoire de France (1607).[10] Robertson notes the commendatory poem written for Grimestone by Chapman which describes the former as ‘his long-lovʼd and worthy friendʼ, and Eccles remarks that Chapmanʼs grandmother, Margaret Grimston née Nodes, was of the same family as the beloved historian.

11If Chapman was driven to writing plays as a means of supporting his translation work his efforts paid off. However, John Wolfall commented of Chapman: ‘at the first being a man of very good parts and expectation hath sithence very unadvisedly spent the most part of his time and his estate in fruitless and vain poetryʼ.[11] Contrary to Wolfallʼs remarks, Chapmanʼs first two extant comedies at the Rose theatre, The Blind Beggar of Alexandria and An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, were financial successes for Henslowe, suggesting popularity among audiences. However, among payments noted in Hensloweʼs accounts for Chapmanʼs plays, some of which are now lost, are three records without statement of their purpose. This suggests that they might be loans, helping to buoy up a second son whose inheritance had long been spent. The first payment, or loan, is recorded on 10 June 1598 for 10s; the second is the same sum paid by Robert Shaa on 1 November of the same year. A third sum of £10 10s is named in a debt signed by Chapman.[12] Despite the success of his comedies, it would seem that perhaps George was in greater financial need than these earnings provided.

12This may have persuaded the Chapman brothers to sell their contested interest in a family property for 120 pounds in 1599, the year the play was printed as An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth by Valentine Simmes. Financial issues were particularly pressing at this time, since the following year Georgeʼs debt to Wolfall again surfaced, resulting in his imprisonment in the Counter at Wood Street.[13]

13The following year of 1601 delivered a further blow to Chapmanʼs fortunes with the execution of his patron, the Earl of Essex, for participation in a revolt against Elizabeth I. Chapman had written dedications to Essex in Seaven Bookes Of The Iliades, a translation of Homer, and in Achilles Shield, both published in 1598. He was appointed as sewer-in-ordinary to Prince Henry in 1604, who quickly became an eager patron and promised Chapman patronage and a pension; neither of these promises was fulfilled when the Prince died aged eighteen in November 1612.

14Dedicating his Epicede on the death of the Prince to Henry Jones also failed to secure Chapman favour. In fact, Jones had been funding Chapman for two years, amassing a total debt of over one hundred pounds by 1612 when Jones decided to leave for Ireland. At this point he wished to settle the debt, drawing up a bond with Georgeʼs brother Thomas as guarantor. The dedication in the Epicede could thus be viewed as the attempted flattery of a man to whom Chapman owed a large quantity of money, or as an attempt to secure patronage which was subsequently blighted by Jonesʼs departure. C. J. Sisson has also suggested that ‘the dedication may have been bought and paid for, in order to give Henry Jones a public place among the patrons of a notable writer of the timeʼ.[14] Despite attempts by Henryʼs brother Peter to reclaim the money, judgement favoured Chapman, and relieved him of the debtʼs burden on 8 February 1622.[15]

15As with the Wolfall suit, the records concerning the Jones case yield further interesting points of information regarding Chapmanʼs character and activity at this time. While Henryʼs younger brother, Roger Jones, protested that ‘whether he [Chapman] may be termed a Poet or not this deponent ... doth not knowʼ, Henry himself described Chapman as ‘a pleasant witty fellow, and one whom this deponent delighted and lovedʼ.[16]

16In 1615, Peter Jones, brother to Henry, began legal proceedings with the help of his lawyer, Richard Holman, ‘against the defendant Thomas Chapman the other defendant absenting himself whereby process could not be served upon himʼ.[17] Thomas, as guarantor, had been called to answer the debt, since George had left London out of fear of being imprisoned again.[18] Despite Georgeʼs sudden reappearance on 12 June 1617 to appeal to the Court of Chancery for time to gather evidence, both Holman and Roger Jones agreed that the younger Chapman brother was ‘of mean or poor estateʼ and ‘doth now live in remote places and is hard to be foundʼ.[19] Butman suggests that since Chapman was unavailable for the majority of the court caseʼs duration and absent from London, a point supported by a lack of extant records of drama performed or published, he may have been in hiding at his brotherʼs inherited house in Hitchin. The dates Butman suggests include autumn 1614 until autumn 1619, save for the 1617 court appearance already mentioned, during which time ‘the only works published by Chapman ... were translations from Musaeus and Hesiod, and the completed Works of Homerʼ.[20]

17Before this suggested exile, Chapman had further courted controversy and unwelcome attention for celebrating the marriage of a badly chosen, but faithfully supported, patron, the Earl of Somerset. The latter began an affair with the Countess of Essex, Frances Devereux, née Howard, who consequently requested a divorce from her husband, citing his impotency as her reason. Chapmanʼs Andromeda Liberata (1614), written to celebrate this marriage, only served to slander the Earl of Essex, who was generally interpreted as being the ‘rockʼ in the poem, from whom Andromeda, or the Countess (by way of a protracted court case), was freed. As a result, Chapman was forced to publish a Justification of the poem, discrediting its malicious interpretations. Despite this furore, Chapman dedicated his Odysses to Somerset the following year.

18Chapmanʼs ‘Invective ... against Mr Ben Jonsonʼ is of uncertain date but must have been written after Jonsonʼs desk was destroyed by fire in 1623, to which incident Chapman makes reference. Bartlett suggests that Chapman may have been taking sides in a significant literary and dramatic controversy between Inigo Jones and Jonson, which culminated in Jonson ceasing to write further court masques for Jones after a quarrel in 1631. Bartlett notes that the argument ‘had been brewing for some time beforeʼ, and suggests that Jonsonʼs criticisms of Chapmanʼs Whole Works of Homer (1616) might have led to the degeneration of their friendship, and thus, Chapmanʼs affiliation with Jones.[21] Certainly, in 1618, Drummond of Hawthornden notes Jonsonʼs venomous dislike of Jones, whilst proclaiming affection for Chapman and praise for his masques.[22]

19Little is known of Chapmanʼs later years, apart from his death one May day, recorded by his faithful dedicator, Inigo Jones, who was honoured in The Divine Poem of Musaeus (1616). John Davies of Hereford accurately summarised Chapmanʼs fortunes in a poem dedicated to the ‘Father of our English Poetsʼ:[23]

But in thy hand too little coin doth lie;

For of all arts that now in London are,

Poets get least in uttering of their ware.

20‘Like an old king in an old-fashion playʼ: Comedyʼs Inheritance

Announcing his intention to ‘point out all my humorous companionsʼ [TLN 50-51], Lemot refers back to dramaʼs rich inheritance as he looks forward to the dayʼs mirth. Quoting from Prestonʼs successful play Cambyses, King of Persia, Lemot assumes royal authority, just as Chapman calls to mind a dramatic authority that reaches far beyond the mid-sixteenth century. After the popularity of Marlovian heroic tragedy diminished, ‘Theatrical taste was on the turnʼ, bringing with it a renewed appetite for comedy.[24] Fledgling dramatists George Chapman and Ben Jonson recognized the potential of Latin comedy to be reinvented, even combining two plots for maximum dramatic complexity. Jonsonʼs first surviving play, The Case Is Altered (1597, revised 1601), borrows Plautusʼ plots of Aulularia and Captivi, while Chapmanʼs later All Fools (1604) is based on Terenceʼs Heautontimorumenos and Adelphi.

21The principal concepts of Roman New Comedy, preserved in Plautus and Terence, filtered down to the Renaissance in essays by Evanthius, Donatus and Diomedes. Their writings can be summarized thus: comedy deals with the private lives of ordinary men without threat of serious violence, danger or death, is often concerned with love, and ends in happy resolution. It therefore differs in diametrically opposed terms from tragedy, which is said to concern public political figures, whose ends are unfortunate. Thomas Heywood provides a classification of genre in his Apology for Actors (1612): ‘Comedies begin in trouble, and end in peace; tragedies begin in calms, and end in tempestʼ (B3, sig F1v). An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth more accurately begins with trouble in the guise of Lemot.

22However, Chapmanʼs play challenges several of the assumptions commonly held about comedy, based on the ‘rulesʼ laid down by the three essayists mentioned above. Although An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth is concerned primarily with private rather than political events, the characters involved are not all ‘ordinaryʼ: many of the characters are lords or counts, and even the king and queen appear as persons of the play. The ordinariness of this play lies in the subject matter: love, marital fidelity, mental and physical health, eating out and having a good time. The threat of violence is very real to the queen, who is convinced that her husbandʼs penis, what Lemot misleadingly refers to as the ‘instrument of procreationʼ [TLN 1629], is about to be removed. The threat affects not only the royal couple, but also the succession and thus the entire country. The threat is diffused within the safe boundaries of mirthful comedy. The quick-thinking Lemot explains he was referring to Martia, for ‘is not she the instrument of procreation, as all women are?ʼ [TLN 1738].

23While An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth is concerned with love, as the definition of comedy dictates, it is principally the love of marital relationships, and predominantly manifests itself as a preoccupation with sex. Wiggins lists sexual content as a novel aspect of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, first introduced in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, but developed in Chapmanʼs next play and further explored in comedy over the next few years. However, study of jigs dating from the late 1580s and early 1590s suggests that this was not such an unknown phenomenon before 1597. Baskervillʼs Elizabethan Jig and Related Song Drama contains jigs whose plots revolve around adultery with neighbours and apprentices. ‘Rowlandʼs Godsonʼ features a wife who has secretly been having sex with the apprentice, and manages to engineer a situation in which her husband, disguised in her clothes, goes to meet the supposedly amorous apprentice to beat him, only to be thwarted by his servantʼs apparent chastity.[25] Of course, the wife has briefed the apprentice in advance, and the husband is therefore reassured of having a faithful wife and servant.

24The wife in ‘Singing Simpkinʼ is nearly caught with not one but two lovers in her house.[26] When the wifeʼs lover, Bluster, knocks at the door, the other lover, Simpkin, is hidden in a chest. When the wifeʼs old husband arrives, Bluster feigns a search for an enemy, and, when he leaves, Simpkin is then able to crawl from his hiding place as the nice man chased by Bluster. The old husband cautions Bluster not to frighten his wife since she is pregnant. From within his chest, Simpkin poses an apt question to the audience: ‘But know you who the father is?ʼ (l. 115). The evidence from these jigs suggests that instead of Chapman doing something completely new, he was utilizing a lower form of comedy in drama. So comic drama did feature sexual content before 1597, but in jig, rather than play, format.

25The anxieties and weaknesses of Labervele and Florila, the Countess and Moren, and the King and Queen, chiefly occupy Lemotʼs intrigue. The union of a young couple, Dowsecer and Martia, is achieved almost by accident through the paternal concern of Labervele, and is less consciously Lemotʼs plot concern than Chapmanʼs. There is a superficial happiness at the end of the play, principally forced by the Kingʼs forgiving speech with its promises of conviviality and unity.

26The ‘comedy of umersʼ

Although it is now generally accepted that Hensloweʼs record of a box office hit called the ‘comedy of umersʼ is Chapmanʼs printed play, An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, it is less widely accepted that Chapman was the instigator of the genre entitled ‘comedy of humoursʼ. Despite a steady voice amongst Chapman scholars attributing him with the creation of the first play of this type, Chapman is often accredited with little more than putting the idea in Jonsonʼs head, and producing work with much room for improvement. Baskervill points out that although in simplistic terms either of the aforementioned playwrights might be credited with inventing the comedy of humours genre, really the development sprang from numerous sources of dramatic and medical literature.[27] As far back as 1567 Baskervill finds extensive use of the word ‘humourʼ in Geffraie Fentonʼs translation of Bandello as Certain Tragical Discourses (1567).[28]

27In the Elizabethan period, the order and machinations of the earthly world received scholarly and theological scrutiny based on ancient and medieval studies. The pyramidal ordering of the created universe placed God at its apex, his authority filtering through the monarch, as head of created society, to the lords, gentry and the lower classes. Extensive study of astronomy and astrology charted the impact of the universe on menʼs lives, in the correct timings for the planting of vegetables and herbs, government by the seasons and the cyclical pattern of the moonʼs orbit. Study was also made of the organization and operation of the body, and it is here that humoural theory was employed.

28In the Induction to Every Man out of His Humour, Asper describes ‘humourʼ thus:

Why, humour (as ʼtis, ens) we thus define it

To be a quality of air or water,

And in itself holds these two properties:

Moisture and fluxure.

(Induction, ll. 86-89, Revels edition)

29Thus, humour was a constantly flowing bodily fluid. Galenʼs theory of humours describes four bodily fluids: black bile, yellow bile or choler, blood and phlegm. These humours were not equally present within the body, but existed in specific proportions, blood being the predominant. If one humour was present to a greater or lesser degree than the perfect balance, imbalance would present itself in a temperamental manifestation, rendering the person melancholic, choleric, sanguine or phlegmatic, thus lucidly described by Asper:

As when some one peculiar quality

Doth so possess a man that it doth draw

All his affects, his spirits, and his powers

In their confluxions all to run one way:

This may truly said to be a humour.

(Induction, ll. 103-07, Revels edition)

30Thus humoural theory was a physiological and psychological explanation for a personʼs temperament, also called ‘humourʼ. Usage of the word increased throughout the second half of the sixteenth century.

31Chapman had experimented with humoural differences when writing The Blind Beggar of Alexandria (1596), the doctored text of which exists in a quarto dated 1598, which strips down the romance plot, preserving mainly the comic interludes. The title page boasts that the blind beggar in question, known as Irus, will be ‘most pleasantly discoursing his variable humours in disguised shapes full of conceit and pleasureʼ. Chapman used the stock plot ingredient of disguise to explore duplicity, aided by humoural traits. Irus plays not only the part of the blind beggar, but also three other characters: Count Hermes, Duke Cleanthes, and Leon the usurer. Chapman made use of garments and humoural disposition to distinguish between the characters played by Irus. Long before Nym was proudly using the new catchword ‘humoursʼ in The Merry Wives of Windsor (1597-8), Bragadino in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria was doing exactly the same thing.

32Overt use of humours in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria has led Robert S. Miola to call it Chapmanʼs trend-setting humours play.[29] However, while Chapman indeed uses humoural temperament as an accessory to characterisation, sketches stressing a characterʼs vice of folly were already popular in the work of Nashe and Lyly.[30] Chapmanʼs innovation in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth was to increase the emphasis on temperament in characterisation, and use this as the basis of the entire plot. Lemot announces ‘this day letʼs consecrate to mirthʼ (2.59) and the resulting action pivots on ‘the underlying premise that people are in themselves funny enough to sustain a comic actionʼ.[31] Chapman does not rely heavily on the medical or theoretical aspects of humours, preferring instead to focus on temperamental differences. Shakespeare, and, to a greater extent, Jonson, were innovators of the new comedy, including references to medicinal humoural theory to increase comic characterisation. In a paper entitled ‘Shakespeareʼs Comedy of Humorsʼ, Northrop Frye begins: ‘The phrase “comedy of humors” belongs to Ben Jonson, so that a paper with such a title has to begin with the relation of Jonsonʼs comedy to Shakespeareʼs.ʼ[32] This introduction argues that since the phrase rightly ‘belongsʼ to George Chapman, any discussion of Ben Jonsonʼs humoural drama should begin with the former playwright.

33Chronologically, Chapman precedes Jonson by experimenting with humours in The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, performed in 1596. At a similar time as Chapman offered An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth to the Admiralʼs Men, Jonson is thought to have produced The Case Is Altered for Pembrokeʼs Men.[33] The repetitious catchphrase for the latter play provides its title, and the alteration of charactersʼ states perhaps fed Jonsonʼs more brutal idea for Every Man out of His Humour‘s systematic purgation of humours. Jonsonʼs well-known response to Chapmanʼs invention, Every Man in His Humour (1598), was probably not the first, nor can The Case Is Altered pose any claim as first humours play.

34The text of Jonsonʼs first surviving comedy, The Case is Altered, was not printed until 1609 and bears evidence of revision, which is thought to have occurred in 1601. This revision principally involves the addition of the character Antonio Balladino, who represents Anthony Munday and rails against the established genre of humours comedy. Jonsonʼs revisions self-consciously attempted to modernize his first play with additional references that cannot have been included in the first performed version, because the genre attacked had yet to be established.

35It seems that Shakespeare was the first to respond to Chapmanʼs humours play by offering The Merry Wives of Windsor to the Chamberlainʼs Men, followed by Much Ado About Nothing (1598). Jonson, who had joined the Admiralʼs Men after the disastrous fall-out over The Isle of Dogs (1597; co-written with Nashe), now had access to, and perhaps contact with, Chapman and his work. Indeed, when the theatres reopened, having escaped threatened demolition in response to Jonson and Nasheʼs lost but presumably seditious play, Chapmanʼs humours comedy was chosen, along with Doctor Faustus and ‘Joroneymoʼ, to encourage audiences back to the Rose.[34]

36Andrew Gurr points to the influence on comedy of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, among other plays, as ‘possibly the clearest single indicator of the power and intensity of the commercial incentive in company repertories through the whole period.ʼ[35] The Chamberlainʼs Men benefited from Shakespeareʼs development of the humours genre in The Merry Wives of Windsor and Much Ado About Nothing, and Jonsonʼs Every Man in His Humour (1598) and Every Man out of His Humour (1599). Henry Porter offered Henslowe The Two Angry Women of Abingdon (1598), while Chapman apparently continued his satire of sartorial affectation in his lost play, The Fountain of New Fashions (1598). The events of summer 1597 might have almost forced the end of lawful drama in London, but without it, and the amalgamation of Pembrokeʼs and the Admiralʼs Men, forcing Jonsonʼs association with Chapman, the genre of comedy might not have received such a radical overhaul at the latter playwrightʼs hands.

37Suddenly, plays containing references to humours on their title pages abounded: The History of Henry the Fourth ... With the humorous conceits of Sir John Falstaff (1598); The Blind Beggar of Alexandria, most pleasantly discoursing his variable humours in disguised shapes full of conceit and pleasure (1598); A pleasant Comedy entitled: An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth (1599); The Pleasant History of the Two Angry Women of Abingdon, with the humorous mirth of Dick Coomes and Nicholas Prouerbs, two Servingmen (1599); The Comical Satire of Every Man out of his Humor (1600); The Shoemakersʼ Holiday, Or the Gentle Craft, with the humorous life of Simon Eyre, shoemaker, and Lord Major of London (1600). As Jason Scott-Warren astutely observes, ‘Humor rapidly became a marketable commodityʼ.[36] The dramatic tide had turned.

38‘Pens as scalpelsʼ: The Anatomization of Humours

Humours shaped not only a genre but, more specifically, a mode of characterization. Gail Kern Paster notes that the language of humoural theory was common currency: ‘Every subject grew up with a common understanding of his or her body as a semipermeable, irrigated container in which humors moved sluggishlyʼ.[37] The humoural imbalance provided dramatists with a way of augmenting the stock characters inherited from classical drama, and facilitated the development of a more individualistic and varied character palette from which to choose. As Madeleine Doran notes, ‘Humour characters of this sort are unlike the broad types of classical comedy; they are narrower and sharperʼ.[38] This specificity heightens realism, and also conveniently ‘makes for quick recognition on the part of reader and spectatorʼ, arousing ‘expectations that can easily be satisfiedʼ.[39]

39But there was another subject that fascinated Renaissance minds, one which links the theatrical event with humoural theory in an even more ‘realisticʼ dramatization. In the Induction to Every Man out of His Humour, Asper scorns popularization of the word ‘humourʼ and its affectation. Cordatus agrees: ‘Now if an idiot/ Have but an apish or fantastic strain,/ It is his humourʼ (Induction, ll. 113-15). As remedy, Asper promises to use the play as a mirror,

As large as is the stage whereon we act,

Where they shall see the timeʼs deformity

Anatomized in every nerve and sinew,

With constant courage and contempt of fear.

(ll. 117-20)

40 Later in the play, the affected courtier Fastidius Brisk promises to introduce an appropriately attired Macilente to Saviolina, ‘the most divine and acute lady of the courtʼ (3.1.113-4). Fastidius holds her up as an ‘anatomy of witʼ, here applied satirically to Saviolina, whose wit can be ‘sinewized and arterizedʼ (l. 117), i.e. dissected and examined in detail and held to be ‘the goodliest model of pleasure that ever was to beholdʼ (ll. 117-18). Perhaps Asper could be accused of taking his promised anatomization to extremes when the character he plays, Macilente, is described by Carlo Buffone as ‘A lank raw-boned anatomyʼ (4.3.136-7), that is, a lean skeleton, devoured by his own envy and bitterness at the fortune and possessions granted others. A similar description is provided of Doctor Pinch in The Comedy of Errors, where Antipholus of Ephesus recalls him as ‘a hungry lean-faced villain,/ A mere anatomy ... / A needy, hollow-eyed, sharp-looking wretch,/ A living dead manʼ (5.1.238-242). Although this account depicts Pinch as a living skeleton, a dramatized memento mori, fascination with the body as machine is also contained within these and Asperʼs words.

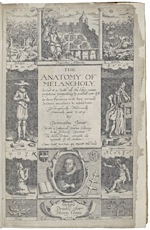

41 The frontispiece to Burtonʼs Anatomy of Melancholy Baskervill records a significant increase in the occurrence of ‘anatomyʼ in the titles of printed works, 1556-1595. The following provides a brief selected list: John Lylyʼs Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1578), Philip Stubbesʼs Anatomy of Abuses (1583), Thomas Nasheʼs Anatomy of Absurdity (1589), and Robert Burtonʼs Anatomy of Melancholy (1621). Devon L. Hodges observes that ‘with violent determination, writers of anatomies used their pens as scalpels to cut through appearances and reveal the mute truth of objects.ʼ[40] The anatomization of character and the vogue for satirical drama and literature was spawned by the increased popularity of medical dissection.

42Although public dissections began in the late fifteenth century, by the mid-sixteenth century, popularity of the spectacle had forced the building of amphitheatres in Europe to seat two or three hundred spectators. Tickets were sold for the event, which could last for up to five days.[41] In London, dissections were carried out in Barber-Surgeonsʼ Hall by the Company of Barber-Surgeons, who were allowed, by license of Parliament, four criminal bodies for anatomical investigation.

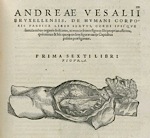

43 Drawings of anatomy theatres of the time reveal similarities between the spectacles of anatomization and drama. For example, in the engraving on the title-page of Vesaliusʼ anatomical study, De Humani Corporis Fabrica (Basel, 1543), the gaze is focused on a central object, a displayed body, which no longer ‘belongsʼ to its owner, while, surrounding the central spectacle, the thronging crowd are boisterous and distracted. Similarities between anatomy theatres and playhouses are not lost on scholars. Michael Neill urges that anatomy theatres ‘deserve to be recognized ... not merely for their scientific significance but as “important chapters in the historical development of the stage”ʼ.[42] To this end, Richard Wilson advocates the Anatomy Theatre at Padua of 1594 as the ‘best preserved Renaissance playhouseʼ.[43] Perhaps it is unsurprising therefore that both Jonathan Sawday and Neill refer to public anatomization in dramatic terms, in Neillʼs words, the ‘drama of dissectionʼ.[44]

44Scott-Warren more specifically names the dramatic genre most similar to anatomization as humours comedy: ‘The way it dissects personality clearly aligns this comedy with the early modern anatomy theatersʼ.[45] Basing his theory on this Renaissance pre-occupation with the voyeuristic exposure of physical and physiological bodies, Scott-Warren also suggests similarities between humours comedy and animal baiting, a rival theatrical entertainment. He points out that the focus of interest in first-hand accounts of such blood sports is not the violence or gore of the spectacle, but the appraisal of characteristics exhibited by each animal as they fight. In fact, the animals are ‘regularly anthropomorphized by way of their surprising qualitiesʼ.[46]

45Similarly, although Jonson is often accused of terrible cruelty to his characters, the purpose of presenting such characters onstage is didactic. Just as dissections contained an instructive element to satisfy the curiosity of a public fascinated with order, Asper promises that characters will be ‘Anatomized in every nerve and sinewʼ (Every Man out of His Humour, Induction, l. 119). In a similar process of theatrical dissection, but perhaps more literally, ‘bearpits and cockpits enabled animals to become objects of knowledge, exposing their inner natures to outward viewʼ.[47] The audience is distanced from the cruelty of tricks and treatment of characters because they are witnessing an anatomization of character, a medical procedure, rather than the torment of individual humans, onstage.

46Thus, corpse, character and animal become the object of the paying publicʼs gaze. Just as a visitor to a bear-baiting event might expect to derive some insight into the nature of bears or dogs, humours comedy also offered to remove superficial layers, permitting ‘privileged glimpses into private selvesʼ.[48] Satiric portraiture takes for granted the notion of specific types and is based, as was the trend for anatomy, on the ‘observation of vitalizing and individualizing detailʼ.[49] The audience is privileged because the satire enables them to disengage from the characters on stage, leading to critical distance and feelings of superiority. It is no surprise, therefore, that humours comedy enjoys playing with notions of spectator and spectacle. Jonson most obviously does this in Every Man out of His Humour, by including a classical Grex, or onstage audience, in the shape of Cordatus and Mitis, whilst also employing Asper as one of the actors. These characters offer multiple frames to the way the audience views the play.

47The theatre, like an operating theatre, promises a glimpse inside a private world: not simply its charactersʼ private walks, houses and local taverns, but inside their very selves. Thus Lemot becomes a doctor of dissection as well as intriguer of action. Or perhaps he is the officiating medic, overseeing the procedure, as his patients, when prompted, dissect themselves and each other through their own folly. The idea of the stage as operating theatre is manifested in Scene 7, where, before the King and his assembled friends, Dowsecer enters on cue and instantly begins to display his humour, like an animal let into the baiting arena. The provision of hose, sword, picture, and codpiece by Lavel serves to remind Dowsecer of the world from which he absents himself. The prompts are also intended to act as a sort of whip, provoking Dowsecerʼs humour.

48Lemot implies animal cruelty at the end of Scene 10 when he promises to ‘jerk the horse you ride onʼ, referring to whoever tries to mend his humour. His words are reminiscent of Alessandro Magnoʼs account of a baiting match in 1562, which begins with the baiting by dogs of a cheap horse ‘and a monkey in the saddleʼ. Magno clearly enjoys this spectacle:

In this sport it is wonderful to see the horse galloping along, kicking up the ground and champing at the bit, with the monkey holding very tightly to the saddle, and crying out frequently when he is bitten by the dogs.[50]

49It seems logical to assume that Lemot is similarly referring to the other characters as monkeys aboard horses, which he is ‘jerkingʼ by use of a whip or dogs. Asper also makes reference to animals when describing the way that ‘humorousʼ or affected characters react: ‘And like galled camels kick at every touchʼ (Induction, l. 132). The physiological and psychological body thus becomes one in both the arenas of animal and human theatre.

50There is a culture of observation at work throughout An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth: not only is Dowsecer spied on, but Lemotʼs wooing of Florila is watched attentively by her jealous husband, Labervele. Jonson experiments most overtly with watching and overhearing in Every Man out of His Humour: throughout the play, characters onstage are observed by Cordatus and Mitis, who sit as privileged commentators, their criticisms in turn informing the Globe audienceʼs response to the action. Just as Lemot describes the amusement provided by an objectified Blanvel, so too does Carlo Buffone question Fastidius Brisk of Sogliardo: ‘How like you him, signor?ʼ (2.1.91), as if presenting an amusing specimen in animal, rather than human, form.

51Within the play proper there are several occasions in which characters hide themselves to witness other action onstage. A case in point is 2.1, in which Carlo Buffone, Sogliardo, Fastidius Brisk and Cinedo hide themselves at the sound of Puntarvoloʼs hounds, heralding the Knightʼs return. The thought of the Knightʼs ridiculous fantasy, in which he pretends to woo his own wife, elicits pure mirth in Sogliardo: he cannot speak he is so consumed with it. The characters hide to observe this courtly ritual, while the Knight and his Lady unwittingly oblige. Yet when the Lady notices their fantasy is being enacted before witnesses (including Fungoso and Sordido, who have since entered) she exclaims and turns indoors (l. 365).

52Further observation occurs after Macilenteʼs initial railing speech, when, at the beginning of 1.2 he lies down on the stage and overhears the action subsequently played upon it, not leaving until he has witnessed Sordido, the grain-hoarding farmer, checking weather predictions in the prognostication. This exit is too early for Mitis, who feels Macilente should have stayed to hear Sordido confess his villainy. Cordatus upbraids Mitis for his misunderstanding of Macilenteʼs envy and, thus, his humour. Throughout the play, Cordatus, who claims to have seen a preview of rehearsals, guides Mitis, and, by implication, the audience, in their appraisal of the characters and action. Mitis is a singled-out audience member, his own musings anatomized by Cordatus for the benefit of the audience proper.

53Not only do these ‘charactersʼ provide commentary and criticism but herald the entrance of characters and inform the audience of scenic locations. At the beginning of the lengthy 3.1, Cordatus advises Mitis, ‘we must desire you to presuppose the stage the middle aisle in Paulʼs, and that [Pointing to the door on which Shift is posting his bills] the west end of itʼ (ll. 1-4). The physicality of St. Paulʼs is thus translated onto the space of the Globe stage.[51]

54The critical and observational role performed by Mitis and Cordatus in Jonsonʼs play can also be identified in Scene 8 of Chapmanʼs comedy of humours. Once the male characters have assembled in Veroneʼs ordinary and are engaged in a game of cards, Lemot and his sidekick Catalian, fresh from an energetic tennis match, begin to discuss the other characters onstage. It is assumed that they occupy a different part of the stage space, or perhaps simply rely on the unrealistic dramatic conventions that permit certain characters to be overheard only by the audience, while the remainder continue oblivious. Helen Ostovich describes the dance-like structure of the Paulʼs walk scene in Every Man out of His Humour, and suggests that in order for the scene to function ‘It is understood that each group of strollers mimes private chat when not delivering lines, and overhears only snatches of other conversations in passingʼ.[52]

55 Similarly in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, Lemot and Catalian circle and observe the other characters, only interrupting the card game to prompt certain characters to respond as predicted to Lemotʼs carefully phrased statements. This is another example of Lemotʼs skill in provoking characters to respond verbally in a way that provides him with ‘excellent sportʼ (TLN 1215). Lemot and Catalian also provide useful information about Rowley, the new character onstage, whose response gives Lemot the idea to predict what each character will say before prompted to do so. As soon as this jest is exhausted, Jaques enters to announce the arrival of a new set of diners. Imagining the sport they will provide him causes Lemot great satisfaction and he falls to the task of engineering the final accumulation of characters at the ordinary with predatory relish.

56Ingestion and Egestion

Humoural theory describes the four humours within the body and advises that a proportional balance of these humours is the ideal healthy state. Any imbalance causes one humour to dominate the others, thus affecting the temperament of the person concerned. Each humour possessed distinguishable properties of temperature and moisture: black bile was cold and dry, producing melancholy; blood, producing a sanguine temperament, hot and wet; hot, dry, yellow bile produced choler; the final category, phlegm, was unsurprisingly thought cold and wet. Popular medicine believed that to help rebalance the humours, one should identify the properties of the predominant humour and balance it by ingesting medicines and foods with oppositional characteristics.

57The link between the stomach and humoural theory apparently goes back to its creator: ‘Galen allegeth a proverb which saith, A gross belly makes a gross understanding, and that this proceeds from nothing else, than that the brain and the stomach are united and chained together with certain sinews, by way of which they interchangeably communicate their damagesʼ.[53] Therefore if a temperamental imbalance can result from bodily substances, the stomach, chief recipient of external factors affecting the body, could cure it. As Paster notes: ‘Bodies were always filled with humors, but the quantity of humors not only depended on such variables as age and gender but also differed from day to day as the body took in food and air, processed them, and released themʼ.[54] So diet could be thought of in medicinal terms, particularly since foods and ingredients themselves were thought to contain similar thermal properties as the humours.

58Henry Buttesʼs diet book, Dietʼs Dry Dinner (1599), contains eight ‘coursesʼ of food, focusing on fruit, herbs, meat, fish, whitemeats, spice, sauce and tobacco. Each individual entry is allocated one page explaining where to acquire it and which part to use, what is benefited or provoked, and how it should be prepared. On the facing page are a series of facts, quotations, and odd pieces of information concerning the individual item. While leeks ‘breed melancholious humoursʼ and are ‘unfit nourishment for any but rustic swainsʼ,[55] cream is ‘hot and moistʼ in the first degree and ‘fitter for youth, choleric and strong stomachs, then [than] the old and rheumaticʼ.[56] Buttes advises that spice is generally not good for those of a choleric temper since it enflames hot constitutions.

59The modern editor of Gervase Markhamʼs The English Housewife (1615), Michael R. Best, draws attention to the importance of diet to general health in his introduction, and comments on the consecutive chapters on medicine and cookery. Best notes that: ‘Markhamʼs division of the two subjects into different chapters is uncharacteristic of cookery books of the period, which habitually introduce medical remedies into the midst of recipes of a purely culinary natureʼ.[57] He also notes that the opposite is true, with culinary recipes often finding their way into books discussing medicinal preparations.[58]

60Baskervill provides several examples of the use of ‘humourʼ in Fentonʼs Certain Tragical Discourses, which is the first work he finds using the term freely. Among the examples given, it is noticeable that the verb ‘to feedʼ occurs in connection with ‘humourʼ, so that the humours are depicted as a hungry stomach whose appetite requires satisfying: ‘Wherein, I fed the hungry humour of my affection with such alarums and contrariety of conceits, that having by this mean lost the necessary appetite of the stomach and usual desire for sleepʼ.[59] Just as the psychological humour requires feeding to satisfy its desire, the physiological humoural imbalance can be treated by harnessing physical appetite as a method of righting the imbalance and restoring good health of mind and body. Fenton, once again, makes the point, and links both food and humours: ‘Meats ... albeit ... good of themselves, yet, being swallowed in gluttonous sort, they do not only procure a surfeit with unsavoury indigestion, but also, converting our ancient health and force of nature into humours of debility distilling thorough all the parts of the body, do corrupt the blood which of itself afore was pure and without infectionʼ.[60] So the advice when it comes to appetite and diet, familiar even to todayʼs health professionals, is ‘a little bit of everything in moderationʼ. Excess of one food causes imbalance not only because it provides a surfeit of one foodʼs properties, but also because this means the diner is neglecting other health-promoting foods.

61At the beginning of Every Man out of His Humour‘s tavern scene (5.3), Carlo Buffone sings the praises of pork because he argues that man is most like a pig and therefore will gain strength more quickly from eating pork, a point promoted by Galenʼs writings.[61] However, Macilente points out to the rather inebriated Carlo another less appealing similarity between pigs and drunken men. When Fungoso has been released both from debt at the ordinary by Deliro and his humour of hankering after the latest fashion, he first wishes to eat ‘a caponʼs legʼ (5.3.445). In Dietʼs Dry Dinner, Buttes explains that his choice ‘procureth an equal temperature of all the humoursʼ, thus providing physical confirmation of humoural rebalance in Fungosoʼs body. [62] Ken Albala also explains that chicken was easier to digest and therefore good for a delicate system.[63]

62A further example of the phrase ‘you are what you eatʼ is more literally expounded by Carlo Buffone in 2.1, when he supposes Puntarvolo feeds his Lady porridge, for ‘She could neʼer have such a thick brain elseʼ (l. 350). This coincides with Macilenteʼs conclusion concerning Carloʼs theory of pork: if a man eats pork, he may behave like a pig, a point unwittingly illustrated by Carlo at the exact moment of Macilenteʼs criticism.

63In Miolaʼs Revels edition of Every Man in His Humour he comments in 1.1 on the first appearance of the word ‘humourʼ in conjunction with the verb ‘to feedʼ (l. 16) and describes this phenomenon as ‘a common locutionʼ (1.1.16n). Later, in 3.1, Cob and Piso discuss this newly fashionable word ‘humourʼ, what it is and how it must be fed:

Piso. Marry, I'll tell thee what it is, as ʼtis generally received in these days: it is a monster bred in a man by self-love and affectation, and fed by folly.

Cob. How? Must it be fed?

Piso. Oh, ay, humour is nothing if it be not fed. Why, didst thou never hear of that? Itʼs a common phrase, ‘Feed my humourʼ.

(3.1.149-155)

64Words concerning food and consumption are frequently associated with an excess of yellow bile, or the choleric temperament. In Every Man in His Humour, Thorelloʼs brother-in-law, Prospero, is staying at his house, and Thorello complains to his half-brother, Giuliano, about the lodgerʼs revelry. News of this bad behaviour incenses the choleric Giuliano to exclaim proverbially: ‘I could eat my very flesh for angerʼ (1.4.67-8). Miola comments that here Giuliano ‘displays the volatility, irrationality, and potential self-destructiveness of the choleric humourʼ.[64] Bobadilla compounds association of Giuliano with appetite later in the scene by referring to him as a ‘scavengerʼ (l. 118), implying that Giuliano is feeding off his prosperous relative, Thorello. The word also applies to the way Giulianoʼs hungry choler is fuelled by others. Thorello, trying to calm down an irate Giuliano, bids him temper his ‘devouring cholerʼ (l. 144). However, Giuliano does not heed Thorello and becomes carried away by his humour in 4.2, when he storms onto the stage in search of Matheo and Bobadilla in such a rage that he does not see them, furiously muttering as he leaves that he cannot find ‘these bragging rascals!ʼ (ll. 99-100).

65With so much talk of appetite and ingestion of material, it is unsurprising that these humours plays also comment on and use the language of egestion. Complaining about overuse of the word ‘humourʼ, Tucca in Poetaster comments: ‘I would fain come with my cockatrice one day and see a play, if I knew when there were a good bawdy one: but they say you haʼ nothing but humours, revels and satires, that gird and fart at the time, you slaveʼ (3.4.192-5). Tuccaʼs comments suggest that the humours plays merely blow bad air back at the audience, engulfing them in their own odiferous affectations. In Every Man in His Humour, the knowledge that those of a melancholic disposition were often prone to constipation enables a joke involving reference to a close-stool at 2.3.91-2. When Matheo offers the self-proclaimed melancholic Stephano his study for the writing of sonnets, Stephano enquires, almost as unnecessary confirmation of his melancholic state, whether the study has a close-stool, presumably to be used while the sonnet-writing eases his constipation.

66Appropriation of alimentary discourse allows the whole of the digestive system to be referred to, not just the mouth and stomach. In Every Man in His Humour, Bobadilla refers in his rage to the recently fled water-bearer, Cob, as ‘a turd, an excrement!ʼ (3.2.119). Cob meanders through the day, carrying water to the various dwelling places of the city, working his way through its streets with his fluid load. In Every Man out of His Humour, Asper provides a clear definition of humour as ‘Moisture and fluxureʼ (Induction, ll. 87-89). As often as humour is referred to in conjunction with the verb ‘to feedʼ it is also described in its fluid state, or ‘streamʼ. Humoural liquids course through menʼs bodies just as Cob carries water through the cityʼs streets.

67Given the connection between humoural theory and the alimentary system, it is perhaps unsurprising that the characters in two humours comedies, An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth and Every Man out of His Humour, end up in a public eating house. When Sogliardo expresses interest in visiting an ordinary in Every Man out of His Humour, Carlo Buffone launches into a monologue of advice from which Rowley, another novice of the ordinary, might have benefited. The ordinary in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth becomes the focal mid-point of the play, since Lemot has contrived for all the characters to converge on it, either within, for a meal, or without, to call their various relatives away. In balance, the celebratory festivity suggested by the King at the end of play smoothes over all tensions, promising reconciliation, and offers feasting as a way of spreading social and humoural equilibrium. This royal patronage ensures that normal societal boundaries will be observed, in direct opposition to the chaos caused by Lemotʼs organisation of a similar meal.

68While it might be perfectly acceptable for married and single men to congregate at the local alehouse or ordinary, respectable women could visit only within the boundary of social convention. Attendance with oneʼs husband was acceptable, as was a visit to break a journey, as part of a family celebration, or in a group.[65] Suitable company was the key to a womanʼs acceptable visit to the alehouse. The furtiveness and hypocrisy with which Florila plans her trip to the ordinary is therefore all the more scandalous. She lies to her husband, pretending she and Martia are going to fast in her private garden, when actually they are going to the ordinary to meet the King and Lemot in private. Of equally low reputation is the woman who allows her husband to go to the ordinary, as the Countess does, only to retrieve him later. Peter Clark observes that ‘A woman who went to the tippling house to call her husband home was likely to meet an extremely hostile receptionʼ.[66]

69When Lemot informs the Countess that her husband is associating with women, and in particular ‘that light hussy Martiaʼ (TLN 1364-1365), he is highlighting the other sort of women who frequent ordinaries, namely prostitutes. In some alehouses, Clark argues, a sociable female partner boosted a hostʼs business.[66] She might even be required to satisfy more than her customerʼs dietary needs. The uneasiness with which Veroneʼs Maid, carrier of his child, fills this role is obvious from her exchange with Catalian. When he advances for a kiss, she shyly protests, ‘Away, sir, fie, for shameʼ (TLN 1155), and it is at this point he notes from close contact that she is pregnant.

70The new fashion for smoking tobacco could frequently be observed in ordinaries and alehouses both on and off stage.[67] More than simply a popular pastime, tobacco was noted and advocated for its medicinal properties. Bobadilla describes it as an antidote to the most deadly poison in Florence, good for gangrenous wounds, and the dispelling of bad humours and badly digested foods (3.2.71-90). Despite impressing the eager Stephano, Bobadilla prompts a very different response from Cob, who comments that tobacco is ‘good for nothing but to choke a man and fill him full of smoke and embersʼ (ll. 99-100). One unlucky smoker ‘voided a bushel of soot yesterday, upward and downwardʼ (ll. 103-04). Cobʼs objections prompt an outburst from Bobadilla, and in the following scene nearly get him jailed by Doctor Clement, such is the feeling in favour of this wonder drug.

71Chapman introduces tobacco to the ‘ordinaryʼ scene in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, when Berger asks Verone for some (TLN 1105-1106). Verone in turn delegates the task of drying a leaf to his son, which enables a delightful joke. The boy replies that they havenʼt got any tobacco, despite Verone assuring Berger that he had ‘The best in townʼ (TLN 1107). In response, Verone desperately hisses his aside, ‘Dry a dock leafʼ (TLN 1109), at which point the boy exits and returns with a pipe. There are no directions for Berger to light the pipe onstage: perhaps he will have to wait for the ‘tobaccoʼ to dry.

72A great deal of fuss surrounds the use of tobacco as designator of status and securer of a womanʼs admiration in Every Man out of His Humour. Fastidius Brisk insists on smoking in front of Saviolina, puffing on his pipe as a form of punctuation (3.3). Despite this fashionable affectation, Saviolina protests that she loves ‘not the breath of a woodcockʼs headʼ (ll. 132-33), referring to the smokerʼs bad breath and also possibly the pipeʼs carved bowl. Bellafront, in 1 Honest Whore, more emphatically claims that tobacco ‘makes your breath stink like the piss of a foxʼ (TLN 830-31). Instead of impressing Saviolina, Fastidiusʼ smoking causes her to exit.

73Jonsonʼs plays make plain the importance for any would-be gentleman to be seen smoking. Thus, in Every Man out of His Humour, Shift is hired in 3.1 to give Sogliardo, the aspiring gent, smoking lessons. Just as going to an ordinary is considered by Sogliardo the mark of a gentleman, for ‘they say there resorts your most choice gallantsʼ (3.1.495-6), smoking is also imperative. Hence reference to it by the brash Berger, and the more timid Rowleyʼs confession that for him this is the first time he has visited an ordinary, in Scene 8 of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth.

74The fashion for tobacco wasnʼt simply thought to be affectation. When it was first introduced, writers such as Buttes advocated its medical blessings:

It cureth any grief, dolor, oppilation, impostume, or obstruction proceeding of cold or wind, especially in the head or breast. The leaves are good against the migraine, cold stomachs, sick kidneys, toothache, fits of the mother, naughty breath, scaldings or burnings ... The fume taken in a pipe is good against rheums, catarrhs, hoarseness, ache in the head, stomach, lungs, breast; also in want of meat, drink, sleep, or rest.[68]

75In particular, smoking was thought to aid phlegmatics, since it caused the expulsion of excess phlegm. That smoking caused the production of phlegm, rather than simply encouraged its ejection, was unknown at the time. In 3.1 of Every Man out of His Humour, Shift explains St Paulʼs is his private phlegm-spitting place, after ‘taking an ounce of tobacco hard by here with a gentlemanʼ (ll. 26-27).

76However, an overabundance of phlegm was not the key complaint in humours characters. Thomas Mark Grant points out that the main obstacles to mirth in An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth are jealousy and melancholy.[69] More generally these humours are of recurring importance in humours comedy and are discussed at greater length below.

77Melancholy

Perhaps one of the most frequently referred to humours, both physiological and affected, is that of melancholy. In Galenic terms an overabundance of black bile, this humour is commonly identified as gentlemanlike, and thus affected by characters such as Stephano, who worries ‘Am I melancholy enough?ʼ (2.3.99-100). Fastidius Brisk and Sogliardo announce they will affect melancholy in 5.2 of Every Man out of His Humour at the death of Puntarvoloʼs dog, but Macilente dismisses their planned affectation as ridiculous. Miola quotes Jonsonʼs commendatory poem to Nicholas Bretonʼs Melancholic Humours (1600), in which he acknowledges the difference between genuine melancholics and those ‘wearing moods, as gallants do a fashion,/ In these pied times, only to show their brainsʼ.[70]

78Unaware of these criticisms, Stephano introduces himself to Bobadilla and Matheo as ‘somewhat melancholyʼ (2.3.71-2), as a clumsy indication of his gentlemanly status. Matheo indulges Stephanoʼs affectation by agreeing that ‘itʼs your only best humour, sir. Your true melancholy breeds your perfect fine wit, sirʼ (ll. 80-81). Matheo continues by sympathising with Stephano: he too suffers from melancholy and occupies his afflicted time with writing ‘your half-score or your dozen of sonnets at a sittingʼ (l. 84). Matheoʼs false affectation is of course rendered all the more deceitful when he is exposed not as an original poet, but one who copies other poetsʼ work and claims it as his own.

79Labesha similarly affects a very self-conscious form of melancholy when he discovers that the woman he idolises, Martia, has attended the ordinary. After informing her father of her whereabouts, he announces his intentions:

I will in silence live a man forlorn,

Mad, and melancholy as a cat,

And nevermore wear hat-band on my hat! (TLN 1398-1399)

80 The frontispiece to Burtonʼs Anatomy of Melancholy (1621) shows the melancholy lover with hat pulled down and his arms folded. References to the lover abound in Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, where Moth describes him thus: ‘with your hat penthouse-like oʼer the shop of your eyes, with your arms crossed on your thin-belly doublet like a rabbit on a spit, or your hands in your pocket like a man after the old paintingʼ (3.1.15-19).[71] Lemot describes Blanvelʼs humour as the repetition of words spoken ‘to a syllable after him of whom he takes acquaintanceʼ (TLN 66), and his retreat to the wall or chimney, ‘standing folding his armsʼ (TLN 76-77). Perhaps this indicates that Blanvel, like Labesha, is also affecting the melancholy lover. In Loveʼs Labourʼs Lost, Berowne refers to Cupid as ‘lord of folded armsʼ (3.1.176). In the Induction to Every Man out of His Humour, Asper asks Mitis if he can spot a melancholic gallant, who ‘Sits with his arms thus wreathed, his hat pulled here,/ Cries mew, and nods, then shakes his empty headʼ (ll. 160-61).

81When the melancholic Dowsecer enters quoting Cicero, he is communicating that his sympathies lie in Stoic philosophy, thereby lauding reason and the suppression of all strong emotions. Dowsecerʼs entrance is preceded by that of the King, who expresses anguish at his own lack of reason: ‘And such are all the affections of love/ Swarming in me, without command or reasonʼ (TLN 779-780). This is the first time that Lemot and the King are together onstage, and it is clear that while the King suffers from similar stoical agonies as Dowsecer, Lemotʼs task is to boost the Kingʼs mood and distract him from these melancholic thoughts.

82 Indeed, when Dowsecer enters and begins to speak, his monologue is interspersed with approving comments from the King. The quotation from Cicero also helps to explain Dowsecerʼs musings not simply as melancholic, but as stoical. The sword and items of apparel placed before Dowsecer prompt speeches declaring his dislike of the irrational, while the picture is rendered safe from wounding his affections because of the superficiality of painting which also occupies Hamletʼs mind. However, when Dowsecer comes into contact with a real woman, Martia, the strong emotions he has been attempting to keep in check overwhelm him: ‘What have I seen? How am I burnt to dust/ With a new sun, and made a novel phoenixʼ (TLN 962-963).

83Dowsecer next enters in Scene 14, utterly transformed into a passionate lover: ‘Iʼll geld the adulterous goat, and take from him/ The instrument that plays him such sweet musicʼ (TLN 1704-1705). The other characters onstage assume Dowsecer refers to the King, since he is with Martia, but this suggestion confuses Dowsecer. The identity of the ‘adulterous goatʼ is therefore unknown, as is the catalyst for Dowsecerʼs sudden, angered appearance. Perhaps this omission points again to a pre-theatrical copy text.

84In Scene 11, Labesha is seen fulfilling his claim, affecting melancholy in the vein of Dowsecer in Scene 7. Like Dowsecer, Labesha begins his speech with a Latin quotation, but his contemplation is interrupted by espial of the cream and spiced cake left in his path by Verone, Catalian and Berger. These are eaten with appetite and forced protestations from Labesha, who pretends he is eating to choke himself as an act of suicide. The choice of cream and spiced cake is perhaps an upmarket version of beer and toast provided by some alehouses as a snack.[72] It also serves a medicinal, corrective purpose of possessing the hot (cake) and wet (cream) properties which should help balance black bileʼs cold dryness. The food provides a joke at the expense of Labesha: according to Galenic principles it should help rebalance his humours and relieve him of his melancholy, except that his humour is falsely self-imposed.

85When Verone devises the plot to tell Labesha that Martia has drowned herself, Catalian, who has assimilated Lemotʼs gift for predicting behaviour, exclaims that Labesha will probably hang himself at the news. The joke is brought to fruition with the appearance of Labesha with a halter about his neck in the final scene. It is unknown whether Labesha had been wearing the halter to inspire sympathy, or whether his loss of Martia prompted a real intention to commit suicide, like Sordido the grain speculator of Every Man out of His Humour. Sordido attempts to hang himself onstage, but is rescued by a number of rustics, just as Labeshaʼs intention to commit suicide is interrupted by Lemot. Labesha reluctantly succumbs to the Kingʼs promise of a better wife for him, but there is no suggestion that his character has gained the insight to change.

86On the other hand, Sordido overhears the rustics cursing him. He realises they hate him and blames his humour: ‘It is that/ Makes me thus monstrous in true human eyesʼ (3.2.104-5), vowing to change his behaviour, and dig up all the grain he had hoarded from his children and the people. He is privileged in taking part in a plot which drives the characters towards self-knowledge, the recognition of wrong-doing, change and reconciliation.

87Jealousy

Wiggins notes that Chapman recognises marital jealousy as a good subject for stage comedy.[73] In An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth there is the protective and manipulative Labervele who plants jewels in his wifeʼs private walk, hoping she, with her staunch religious convictions, will think they have come from heaven. The jewels bear posies advising Florila to stick by her husband and not despair, for Godʼs power is most potent when human strength is low. It is stressed in the play that Florila, his wife, is young, and that Labervele already has a son, Dowsecer, presumably from a previous union. No maternal connection is made between Florila and Dowsecer, and it is likely that Laberveleʼs first wife has died and he has remarried. However, the couple seem to have some reproductive trouble, for which Labervele takes the blame: ‘She longs to have a child, which yet, alas,/ I cannot getʼ (TLN 20-21). Hence Laberveleʼs anxiety for his scholarly son, Dowsecer, to reproduce, and thus continue the family line: Labervele seems convinced his opportunities are over.

88Anxiety about fecundity seems to drive Laberveleʼs desperate attempts to improve his wifeʼs mood and their chances of conceiving, knowing that without children to occupy and satisfy her, she might soon look elsewhere. He encourages her to wear the jewels and a velvet hood, as befits her status, ‘Not to go thus like a milkmaidʼ (TLN 231-232). After her outburst at his vain suggestion, Labervele explains that maybe Florilaʼs reclusiveness and melancholy is the reason why she is not pregnant, suggesting she leave the house and socialise. Florila takes surprisingly quickly to this suggestion, warming to the idea that since the end of marriage is procreation,

... I should sin,

If by my keeping house I should neglect

The lawful means to be a fruitful mother

(TLN 247-249)

89She quickly decides to follow her husbandʼs advice, and he is surprised by the willingness with which she abandons her former course and succumbs to his temptation, thinking it the correct solution.

90Florila similarly abandons her Puritan stance when Lemot attempts to woo her, even devising a system of signs so that her jealous watching husband can be assured of her constancy to him; all the while she is confirming her allegiance to Lemot. While Labervele is debating whether or not he really does want his wife to leave the house, Catalian interrupts, and it is clear how Labervele fills the role of the jealous husband from this point on. He objects to being ‘thrust upon in private walksʼ (TLN 270), and takes an instant dislike to everything Catalian says. Just as Labervele is whipping himself up into a frenzy, Lemot enters, announcing that it is good Christian practice to test fellow Christiansʼ constancy. The following scene exposes Laberveleʼs acute jealousy and his wifeʼs hypocrisy, since Lemot easily wins her over.

91In Every Man in His Humour, Thorello is similarly jealous of his wife, since her brother, who is lodging in the house, frequently invites gallants to visit and make merry. He suspects that, faced with temptation, she might not remain faithful for long. Soon after he has admitted this, he groans, ‘Troth, my head aches extremely on a suddenʼ (1.4.194), which Bianca identifies as ‘this new diseaseʼ (l. 198). Thorello agrees, but knows he is afflicted with fear of cuckoldry, which he goes on to describe as ‘poor mortalsʼ plagueʼ (l. 209), one which infects imagination and memory.

92As Deliro in Every Man out of His Humour turns his house into a shrine for his divine wife with incense and strewn flowers, Thorello talks of Bianca as his treasure and ‘Beautyʼs golden treeʼ (3.1.19). Just as Florila is observed enclosed within her private walk, so are Bianca and Fallace. Ironically, though, Deliro misguidedly worships his wife and is convinced by her fidelity to him, while she is dreaming of Fastidius Brisk, the handsome courtier, and each of his good parts. Only when Deliro is sent to the Counter to release Fastidius is his illusion shattered: Macilente has also sent Fallace to see her idol, and she kisses him just as Deliro enters. Thus the gullible husband is put out of his humour.

93Thorello, on the other hand, leaves his wife Bianca in the house while he goes to attend to his business and asks Piso to inform him if anyone enters the house. It is Cob who tells Deliro that several men have entered his house, to which Deliro hysterically responds ‘A swarm, a swarmʼ (3.3.8), concluding that he has already been cuckolded. This hysteria is comparable with Laberveleʼs confused panic at an associated reference to cuckoldry, when he cries, ‘Thieves, Puritans, murderers!ʼ (TLN 419), whilst ushering his wife indoors.

94Indeed, Thorello displays some of Giulianoʼs choleric heat when Prospero plants the idea in his head that his clothes and wine might have been poisoned. Thorello then displays the exact signs of the cuckoldʼs malady he described, tainting his own thoughts and memories with the notion that Bianca has indeed poisoned his cup and bid him wear that particular suit. Instantly he begins affecting illness and sends for remedies, at which Prospero exclaims: ‘Oh, strange humour! My very breath hath poisoned himʼ (4.3.27-8).[74] Prospero then correctly identifies that ‘His jealousy is the poison he hath takenʼ (l. 40), a point which concurs with Biancaʼs conclusion: ‘If you be sick, your own thoughts make you sickʼ (l. 39).

95The additional problem of this particular illness is that it infects those around the sufferer. Prospero engineers for both Bianca and Thorello to be sent to Cobʼs house on the pretext that the other is having an affair with one of the occupants. The real reason for this is to get the couple out of the house so Lorenzo Junior and Hesperida can meet one another. When the jealous couple arrive at Cobʼs house, Bianca, infected by her husbandʼs jealousy, and acting upon Prosperoʼs suggestion that Thorello is a frequent visitor, assumes that Tib is a waiting-woman to her husbandʼs mistress. Thorello sees Bianca and assumes she has come to meet Lorenzo Senior, when he is actually there looking for his son. The mess cannot be untangled without the help of Doctor Clement.

96In Every Man out of His Humour, Deliro is to discover the truth in Thorelloʼs conclusion, ‘Horns in the mind are worse than on the headʼ (5.3.432). This is also sound advice for Labervele, who perhaps drives his wife to temptation by closeting her up. One might also suggest, as in the case of the old Countess and her youthful husband, that some of these marriages are unsuitable matches, since they involve couples of differing ages and thus breed their own anxieties. Unions between couples such as Dowsecer and Martia, and Lorenzo Junior and Hesperida, are most healthy in promising happiness and fecundity.

97Architects of Intrigue

According to Madeleine Doran, intrigue plays are reliant on ‘disguise, lies, clever excuses, manipulation to get characters together at the right time or keep them separateʼ.[75] This description perfectly fits the action of An Humorous Dayʼs Mirth, whose catalyst is found in an intriguer, also known in Roman comedy as the architectus.[76] Lemot is one such figure, a master-intriguer of plot and persons for the purposes of entertainment: ‘this day letʼs consecrate to mirthʼ (TLN 99) Lemot announces in the second scene of the play. This is the main drive of the plot: to provoke the characters into acting as predicted and enjoy the resulting confusion. Yet Lemotʼs role as intriguer also invests in him the expectation of resolving all problems before he hands his power back to the King at the end of the play.

98 Lemotʼs plan very nearly backfires and causes him to run from the situation he has created. In Scene 14 Lemot brings the Queen and her party to the place where she expects to find the King being threatened with removal of his ‘instrument of procreationʼ (TLN 1736). Encouraged by Lemot, she has interpreted this as referring to the Kingʼs penis. Instead she encounters the angry Dowsecer, intent on gelding an ‘adulterous goatʼ, removing from him ‘The instrument that plays him such sweet musicʼ (TLN 1705). Lemot decides that since this adds truth to his lie, heʼll not flee, but stay to hear the outcome. Fortune lies in Dowsecerʼs choice of words, which corroborate Lemotʼs fiction and excuse him from the otherwise necessary task of explaining himself and perhaps admitting to the erroneous manufacture of lies.

99Although Lemot appears as a new manifestation of the ‘cunning slaveʼ stock character of Roman comedy, his status indicates a merging of categories. Doran claims that ‘The intriguer in English comedy is not often a servant; he is more likely to be one of the principalsʼ.[77] Often referred to derisively by other characters in the play as the Kingʼs ‘minionʼ (TLN 311, 552, 698), Lemotʼs status is as upper class servant to his monarch, and is thus a principal in terms of status and function in both the play and the court.

100Charlotte Spivack invests essential importance in Lemot: ‘[The play] obtains its unity and coherence not so much from the satirical theme as from its intriguer-hero Lemot, who supervises the paradox of “humours” and manipulates the disparate characters in a highly complex plotʼ.[78] Lemot is crucial to the forward movement of plot, and as a uniting presence amongst characters of differing social status and age. The name given to this character is of particular interest. ‘Le motʼ very literally means ‘the wordʼ in French and it is therefore highly appropriate that his chief differentiating quality is his quick-witted talent with language. The use of puns, quick-fire word play, noting other charactersʼ language quirks, predicting speech and use of misleading language are all basic skills in Lemotʼs repartee and also tools with which he advances the plot. Grant points out that ‘Monsieur Verbumʼ (TLN 496), as Martia call him, preys on victims who cannot join in his word games.[79] While Martia rises admirably to the task in Scene 5, her doting guardian, Labesha, is ridiculed and distracted from his charge with flattery.

101Jonathan Hudston goes one step further in his identification of Lemot as ‘the wordʼ, suggesting a link with the opening of Johnʼs Gospel: ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was Godʼ (John 1:1). This point places Lemot even more explicitly in a seat of power, not merely placing the crown of the King upon his head in mock-imitation of Cambyses, but also adorning himself with Godʼs mantle of power. The suggestion would be blasphemous to the original audience and particularly for the playʼs resident Puritan. Lemotʼs assumed role of all-powerful plot orchestrator admittedly places him in an omnipotent position. The Kingʼs melancholy prompts Lemotʼs intrigues as a way of lightening the monarchʼs mood. Thus the departure of the Kingʼs reasoning, which he laments in Scene 7, is indeed a cause for concern, since the power lies in Lemotʼs hands to bring the King back to health with his mirthful remedies. A new order ensues, and the Puritan, whose allegiance is verbally pledged to God, turns her affections to Lemot. In this sense, Lemot really is ‘playingʼ God, as the new subject of her idolatry.

102The importance of an intrigue character like Lemot is summarised by Northrop Frye: ‘Such a character, who needs no motivation because he acts merely for the fun of seeing what will happen, is to comedy what the Machiavellian villain is to tragedy, a self-starting principle of the actionʼ.[80] With his dynamism and humorous predisposition, Lemot has been likened to the medieval Vice figure by several commentators.[81] Spivack points to him being referred to as ‘Monsieur Satanʼ (TLN 689). A key factor in Lemotʼs character is that although he provokes confusion and distress in some of his victims, his principal aim is to amuse himself and the King. The focus is not so much on good versus evil, as on firing warning shots suggestive of the potential each character has to be tempted into sin. Doran describes the English intriguer as ‘more apt to be a healthful exposer of menʼs follies than a malicious instigator of themʼ.[82] Because the focus of this action is comedic, Lemot only pushes so far. The threat of temptation is welcomed by Florila, and, although she is eager to sin with Lemot, he withdraws, biting her hand in place of a kiss. Similarly, Moren is enticed to the ordinary, but Lemot knows that since so many people will be present, including the doting King, Moren will have no chance to betray his suspicious wife. Thus, Grant summarises Lemot as ‘intriguer, expositor of folly and lord of misruleʼ.[83]

103But the intriguer doesnʼt merely invent the plot. His desire for mirth prompts him to share it with his offstage audience. Lemotʼs continual commentary and critical display of character invites detachment and satirical evaluation of onstage action from the audience. As Brian Gibbons observes, ‘Lemotʼs function is also to effect the isolation of a character, from his stage companions and from the audienceʼs sympathyʼ.[84] He does this most effectively with the display of Blanvelʼs humour in Scene 2 and the taunting of Labesha in Scene 8.